Archive for the ‘reaction mechanism’ Category

Wednesday, November 12th, 2014

In London, one has the pleasures of attending occasional one day meetings at the Burlington House, home of the Royal Society of Chemistry. On November 5th this year, there was an excellent meeting on the topic of Challenges in Catalysis, and you can see the speakers and (some of) their slides here. One talk on the topic of Direct amide formation – the issues, the art, the industrial application by Dave Jackson caught my interest. He asked whether an amide could be formed directly from a carboxylic acid and an amine without the intervention of an explicit catalyst. The answer involved noting that the carboxylic acid was itself a catalyst in the process, and a full mechanistic exploration of this aspect can be found in an article published in collaboration with Andy Whiting's group at Durham.[1] My after-thoughts in the pub centered around the recollection that I had written some blog posts about the reaction between hydroxylamine and propanone. Might there be any similarity between the two mechanisms?

(more…)

References

- H. Charville, D.A. Jackson, G. Hodges, A. Whiting, and M.R. Wilson, "The Uncatalyzed Direct Amide Formation Reaction – Mechanism Studies and the Key Role of Carboxylic Acid H‐Bonding", European Journal of Organic Chemistry, vol. 2011, pp. 5981-5990, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejoc.201100714

Tags:Andy Whiting, Dave Jackson, dielectric, Durham, energy profile, free energy barrier, London, non-polar solution, PDF, Royal Society of Chemistry

Posted in reaction mechanism | 6 Comments »

Thursday, November 6th, 2014

Solvolytic mechanisms are amongst the oldest studied, but reproducing their characteristics using computational methods has been a challenging business. This post was inspired by reading Steve Bachrach’s post, itself alluding to this aspect in the title “Computationally handling ion pairs”. It references this recent article on the topic[1] in which the point is made that reproducing the features of both contact and solvent-separated ion pairs needs a model comprising discrete solvent molecules (in this case four dichloromethane units) along with a continuum model.

(more…)

References

- T. Hosoya, T. Takano, P. Kosma, and T. Rosenau, "Theoretical Foundation for the Presence of Oxacarbenium Ions in Chemical Glycoside Synthesis", The Journal of Organic Chemistry, vol. 79, pp. 7889-7894, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo501012s

Tags:10.1021, Steve Bachrach

Posted in reaction mechanism | No Comments »

Saturday, September 6th, 2014

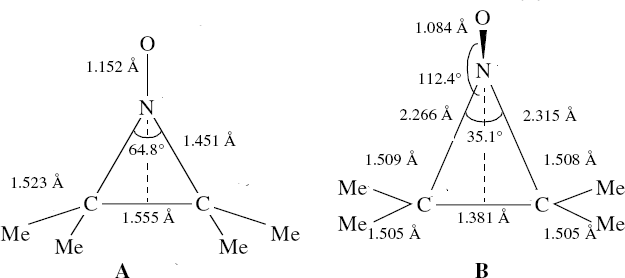

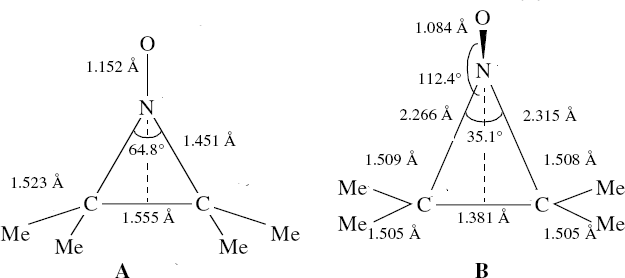

In the previous posts, I explored reactions which can be flipped between two potential (stereochemical) outcomes. This triggered a memory from Alex, who pointed out this article from 1999[1] in which the nitrosonium cation as an electrophile can have two outcomes A or B when interacting with the electron-rich 2,3-dimethyl-2-butene.  NMR evidence clearly pointed to the π-complex A as being formed, and not the cyclic nitrosonium species B (X=Al4–). If you are wondering where you have seen an analogy for the latter, it would be the species formed when bromine reacts with an alkene (≡ Br+, X=Br– or Br3–). The two structures are shown below[1]

NMR evidence clearly pointed to the π-complex A as being formed, and not the cyclic nitrosonium species B (X=Al4–). If you are wondering where you have seen an analogy for the latter, it would be the species formed when bromine reacts with an alkene (≡ Br+, X=Br– or Br3–). The two structures are shown below[1]  Since the topic that sparked this concerned pericyclic reactions, it seemed possible that if it had been formed, species B would immediately undergo a pericyclic electrocyclic reaction to form the rather odd-looking cation C, which might then be trapped by eg X(-) to form the nitrone D. So this post is an exploration of what happens when X-NO (X= CF3COO, trifluoracetate) interacts with 2,3-dimethyl-2-butene, as an illustration of what can be achieved nowadays from about 2 days worth of dry-lab computation as a prelude to e.g. an experiment in the wet-lab (it would take a little more than two days to achieve the latter I suspect). Hence computationally directed synthesis. The model is set up as ωB97XD/6-311G(d,p)/SCRF=chloroform. A transition state is located[2] and the resulting IRC (below) [3] does not quite have the outcome the above scheme would suggest.

Since the topic that sparked this concerned pericyclic reactions, it seemed possible that if it had been formed, species B would immediately undergo a pericyclic electrocyclic reaction to form the rather odd-looking cation C, which might then be trapped by eg X(-) to form the nitrone D. So this post is an exploration of what happens when X-NO (X= CF3COO, trifluoracetate) interacts with 2,3-dimethyl-2-butene, as an illustration of what can be achieved nowadays from about 2 days worth of dry-lab computation as a prelude to e.g. an experiment in the wet-lab (it would take a little more than two days to achieve the latter I suspect). Hence computationally directed synthesis. The model is set up as ωB97XD/6-311G(d,p)/SCRF=chloroform. A transition state is located[2] and the resulting IRC (below) [3] does not quite have the outcome the above scheme would suggest.

Neither A nor B is formed; instead it is the tetrahedral species E, which is ~15 kcal/mol endothermic.

Neither A nor B is formed; instead it is the tetrahedral species E, which is ~15 kcal/mol endothermic.  I should immediately point out that this is not inconsistent with the formation of A as previously characterised[1]. That is because this experiment was conducted with a non-nucleophilic counter-anion (X=Al4–), whereas in the computational simulation above, we have a nucleophilic anion (X= CF3CO2–). What a difference the inclusion of a counter-ion in the calculation can have! The barrier however (~35 kcal/mol) is a little too high for a facile thermal reaction. In the second of this two-stage reaction, E now ring-opens to form the anticipated D[4] with quite a small barrier of ~6 kcal/mol, but a highly exothermic outcome. I ask this question about it; can this still be described as a pericyclic process? (there is some analogy to the electrocyclic ring opening of a cyclopropyl tosylate).

I should immediately point out that this is not inconsistent with the formation of A as previously characterised[1]. That is because this experiment was conducted with a non-nucleophilic counter-anion (X=Al4–), whereas in the computational simulation above, we have a nucleophilic anion (X= CF3CO2–). What a difference the inclusion of a counter-ion in the calculation can have! The barrier however (~35 kcal/mol) is a little too high for a facile thermal reaction. In the second of this two-stage reaction, E now ring-opens to form the anticipated D[4] with quite a small barrier of ~6 kcal/mol, but a highly exothermic outcome. I ask this question about it; can this still be described as a pericyclic process? (there is some analogy to the electrocyclic ring opening of a cyclopropyl tosylate).

So what are the conclusions? Well, because of the rather high initial barrier, the alkene will need activation (by electron donating substituents, perhaps OMe) for the reaction to become more viable. But if it works, it could be an interesting synthesis of nitrones (I have not yet searched to find out if the reaction is actually known).

So what are the conclusions? Well, because of the rather high initial barrier, the alkene will need activation (by electron donating substituents, perhaps OMe) for the reaction to become more viable. But if it works, it could be an interesting synthesis of nitrones (I have not yet searched to find out if the reaction is actually known).

References

- G.I. Borodkin, I.R. Elanov, A.M. Genaev, M.M. Shakirov, and V.G. Shubin, "Interaction in olefin–NO+ complexes: structure and dynamics of the NO+–2,3-dimethyl-2-butene complex", Mendeleev Communications, vol. 9, pp. 83-84, 1999. https://doi.org/10.1070/mc1999v009n02abeh000995

- H.S. Rzepa, "C8H12F3NO3", 2014. https://doi.org/10.14469/ch/24979

- H.S. Rzepa, "Gaussian Job Archive for C8H12F3NO3", 2014. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1162797

- H.S. Rzepa, "Gaussian Job Archive for C8H12F3NO3", 2014. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1162676

Tags:CF 3, CF 3 CO, COO, simulation

Posted in pericyclic, reaction mechanism | 2 Comments »

Monday, August 18th, 2014

This post, the fifth in the series, comes full circle. I started off by speculating how to invert the stereochemical outcome of an electrocyclic reaction by inverting a bond polarity. This led to finding transition states for BOTH outcomes with suitable substitution, and then seeking other examples. Migration in homotropylium cation was one such, with the “allowed/retention” transition state proving a (little) lower in activation energy than the “forbidden/inversion” path. Here, I show that with two electrons less, the stereochemical route indeed inverts. First, a [1,4] alkyl shift with inversion at the migrating carbon (ωB97XD/6-311G(d,p)/SCRF=chloroform); as a four-electron process, this is the “allowed” route.[1]

First, a [1,4] alkyl shift with inversion at the migrating carbon (ωB97XD/6-311G(d,p)/SCRF=chloroform); as a four-electron process, this is the “allowed” route.[1]  The “forbidden” route corresponds to retention of configuration at the migrating carbon.[2]

The “forbidden” route corresponds to retention of configuration at the migrating carbon.[2]  The barriers for each process can be seen below from the IRCs. That for inversion is ~4.5 kcal/mol lower than retention. This nicely transposes the values for the six-electron homologue shown in the previous post.

The barriers for each process can be seen below from the IRCs. That for inversion is ~4.5 kcal/mol lower than retention. This nicely transposes the values for the six-electron homologue shown in the previous post.

There is one more nugget of insight that can be extracted. The start/end-point for the six-electron process (homotropylium cation) was, as the name implies, homoaromatic. Now, with a four-electron system we also have an inverse. Nominally, we should now end with homo-antiaromaticity (but see [3]). But antiaromaticity is avoided whenever possible, and so the homoaromatic bond observed in homotropylium is not formed. It resolutely remains a σ-bond (1.48Å) thus sequestering two electrons, and the remaining two electrons simply form a delocalised allyl cation. With the six-electron homotropylium, reactant/product were stabilised by that additional (homo)aromaticity, thus inducing a relatively high barrier. With the four-electron system here, no such reactant/product stabilisation occurs, and hence the reaction barriers are now significantly lower. A rather neat pedagogic example.

There is one more nugget of insight that can be extracted. The start/end-point for the six-electron process (homotropylium cation) was, as the name implies, homoaromatic. Now, with a four-electron system we also have an inverse. Nominally, we should now end with homo-antiaromaticity (but see [3]). But antiaromaticity is avoided whenever possible, and so the homoaromatic bond observed in homotropylium is not formed. It resolutely remains a σ-bond (1.48Å) thus sequestering two electrons, and the remaining two electrons simply form a delocalised allyl cation. With the six-electron homotropylium, reactant/product were stabilised by that additional (homo)aromaticity, thus inducing a relatively high barrier. With the four-electron system here, no such reactant/product stabilisation occurs, and hence the reaction barriers are now significantly lower. A rather neat pedagogic example.

References

- H.S. Rzepa, "Gaussian Job Archive for C8H11(1+)", 2014. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1142175

- H.S. Rzepa, "Gaussian Job Archive for C8H11(1+)", 2014. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1142174

- C.S.M. Allan, and H.S. Rzepa, "Chiral Aromaticities. A Topological Exploration of Möbius Homoaromaticity", Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, vol. 4, pp. 1841-1848, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1021/ct8001915

Tags:activation energy, reactant/product

Posted in pericyclic, reaction mechanism | 2 Comments »

Tuesday, August 12th, 2014

One thing leads to another. Thus in the previous post, I described a thermal pericyclic reaction that appears to exhibit two transition states resulting in two different stereochemical outcomes. I noted that another such reaction appeared to be a [1,6] carousel migration in homotropylium cation,[1] where transition states for both retention and inversion of the configuration of the migrating group (respectively formally allowed and forbidden) were reported (scheme below). Here I explore this system further.  Firstly, the pathway leading to inversion.[2] The reaction path (ωB97XD/6-311G(d,p)/SCRF=chloroform) has got a very odd (table-top mountain) shape, whereby the region of the transition state (IRC = 0.0) is very flat, and the region close to reactant and (identical) product is very steep. The gradient norm shows this best, with sharp spikes at IRC ± 4.2. Something clearly is happening here to cause this behaviour. Before moving on to analyze this, I want you first to observe the methyl groups below. Note how one of them rotates at the start of the process, and the other at the end. I have elsewhere called this behaviour the methyl flag, and it is due to stereoelectronic re-alignments of the C-H groups accompanying the changes in the conjugated array.

Firstly, the pathway leading to inversion.[2] The reaction path (ωB97XD/6-311G(d,p)/SCRF=chloroform) has got a very odd (table-top mountain) shape, whereby the region of the transition state (IRC = 0.0) is very flat, and the region close to reactant and (identical) product is very steep. The gradient norm shows this best, with sharp spikes at IRC ± 4.2. Something clearly is happening here to cause this behaviour. Before moving on to analyze this, I want you first to observe the methyl groups below. Note how one of them rotates at the start of the process, and the other at the end. I have elsewhere called this behaviour the methyl flag, and it is due to stereoelectronic re-alignments of the C-H groups accompanying the changes in the conjugated array.

The homotropylium cation is said to be homoaromatic, indicating that cyclic conjugation can be maintained across a ring in which the σ framework is interrupted at one point. A NICS probe placed at the ring critical point of this molecule reveals a chemical shift of -11.3 ppm[3], very similar to eg that obtained for benzene itself. The three highest doubly occupied NBOs (below) show two normal π-type orbitals and one rather different one that spans the homo-bond (the MOs, before you ask, are a bit of a mess, with lots of mixed contributions from other parts of the σ framework).

The homotropylium cation is said to be homoaromatic, indicating that cyclic conjugation can be maintained across a ring in which the σ framework is interrupted at one point. A NICS probe placed at the ring critical point of this molecule reveals a chemical shift of -11.3 ppm[3], very similar to eg that obtained for benzene itself. The three highest doubly occupied NBOs (below) show two normal π-type orbitals and one rather different one that spans the homo-bond (the MOs, before you ask, are a bit of a mess, with lots of mixed contributions from other parts of the σ framework).

(more…)

References

- A.M. Genaev, G.E. Sal’nikov, and V.G. Shubin, "Energy barriers to carousel rearrangements of carbocations: Quantum-chemical calculations vs. experiment", Russian Journal of Organic Chemistry, vol. 43, pp. 1134-1138, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1134/s1070428007080076

- H.S. Rzepa, "Gaussian Job Archive for C10H13(1+)", 2014. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1134556

- H.S. Rzepa, "Gaussian Job Archive for C10H13(1+)", 2014. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1135694

Tags:chemical shift, higher energy, Sangean Table Top Portable Audio Device

Posted in pericyclic, reaction mechanism | 5 Comments »

Sunday, August 10th, 2014

In my first post on the topic, I discussed how inverting the polarity of the C-X bond from X=O to X=Be (scheme below) could flip the stereochemical course of the electrocyclic pericyclic reaction of a divinyl system. This was followed up by exploring what happens at the half way stage, i.e. X=CH2, the answer being that one gets an antarafacial pathway as with X=O. Here I fill in another gap, X=BH to see if a metaphorical microscope can be used to view the actual region of the “flip” to a suprafacial mode. This time, uniquely, it proved possible to locate TWO transition states for this process, one suprafacial[1] and one antarafacial[2], this latter being 10.5 kcal/mol lower in ΔG† (ωB97XD/6-311G(d,p)/SCRF=dichloromethane). It is quite rare to be able to find BOTH stereochemical outcomes of a thermal pericyclic reaction.‡

This time, uniquely, it proved possible to locate TWO transition states for this process, one suprafacial[1] and one antarafacial[2], this latter being 10.5 kcal/mol lower in ΔG† (ωB97XD/6-311G(d,p)/SCRF=dichloromethane). It is quite rare to be able to find BOTH stereochemical outcomes of a thermal pericyclic reaction.‡

(more…)

References

- H.S. Rzepa, "Gaussian Job Archive for C5H7B", 2014. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1133933

- H.S. Rzepa, "Gaussian Job Archive for C5H7B", 2014. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1133934

Tags:Alex Genaev, Hawaii, HB

Posted in pericyclic, reaction mechanism | No Comments »

Sunday, April 20th, 2014

Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate reacts with carbon dioxide to produce 3-keto-2-carboxyarabinitol 1,5-bisphosphate as the first step in the biochemical process of carbon fixation. It needs an enzyme to do this (Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, or RuBisCO) and lots of ATP (adenosine triphosphate, produced by photosynthesis). Here I ask what the nature of the uncatalysed transition state is, and hence the task that might be facing the catalyst in reducing the activation barrier to that of a facile thermal reaction. I present my process in the order it was done‡.

(more…)

Tags:1M solutions, carbon fixation, chair, chemist, energy, free energy, low energy, low energy sink, lower energy conformation, lower energy isomer, Peter Medawar, phosphate

Posted in Interesting chemistry, reaction mechanism | 1 Comment »

Tuesday, April 15th, 2014

The journal of chemical education can be a fertile source of ideas for undergraduate student experiments. Take this procedure for asymmetric epoxidation of an alkene.[1] When I first spotted it, I thought not only would it be interesting to do in the lab, but could be extended by incorporating some modern computational aspects as well.

(more…)

References

- A. Burke, P. Dillon, K. Martin, and T.W. Hanks, "Catalytic Asymmetric Epoxidation Using a Fructose-Derived Catalyst", Journal of Chemical Education, vol. 77, pp. 271, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed077p271

Tags:chemical education, energy, free energy, Shi Fructose

Posted in Interesting chemistry, reaction mechanism | 2 Comments »

Wednesday, March 12th, 2014

My previous post related to the aromatic electrophilic substitution of benzene using as electrophile phenyl diazonium chloride. Another prototypical reaction, and again one where benzene is too inactive for the reaction to occur easily, is the catalyst-free bromination of benzene to give bromobenzene and HBr.

(more…)

Tags:activation energy, animation, aromatic, Boris Galabov, co-author, electrophilic, lowest energy solution, o/p director of aromatic electrophilic substitution, Paul Schleyer, pence, substitution

Posted in Interesting chemistry, reaction mechanism | 8 Comments »

Saturday, March 8th, 2014

The diazo-coupling reaction dates back to the 1850s (and a close association with Imperial College via the first professor of chemistry there, August von Hofmann) and its mechanism was much studied in the heyday of physical organic chemistry.[1] Nick Greeves, purveyor of the excellent ChemTube3D site, contacted me about the transition state (I have commented previously on this aspect of aromatic electrophilic substitution). ChemTube3D recruits undergraduates to add new entries; Blue Jenkins is one such adding a section on dyes.

(more…)

References

- S.B. Hanna, C. Jermini, H. Loewenschuss, and H. Zollinger, "Indices of transition state symmetry in proton-transfer reactions. Kinetic isotope effects and Bronested's .beta. in base-catalyzed diazo-coupling reactions", Journal of the American Chemical Society, vol. 96, pp. 7222-7228, 1974. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00830a009

Tags:covalent systems, first professor, free energy, Imperial College, lowest energy pose, Nick Greeves, professor of chemistry

Posted in reaction mechanism | 2 Comments »