The annual “Molecules of the Year” selections are available for the year 2025. A theme was elemental allotropes and one such was carbon in the form of C48 stabilised by formation of a catenane C48.M3 (M = red ligand below)[1] – it was not possible however to crystallise C48.M3. When “unmasked” by removal of the M ligand, the true allotrope C48 had a solution half-life of about 1 hour at 20°C. This follows the reports from 2019 onwards of a series of smaller cyclo[n]carbon allotropes, (n=6,10,12,13,14,16,18,20,26)[2],[3] which were only characterised on a solid surface and not in solution.

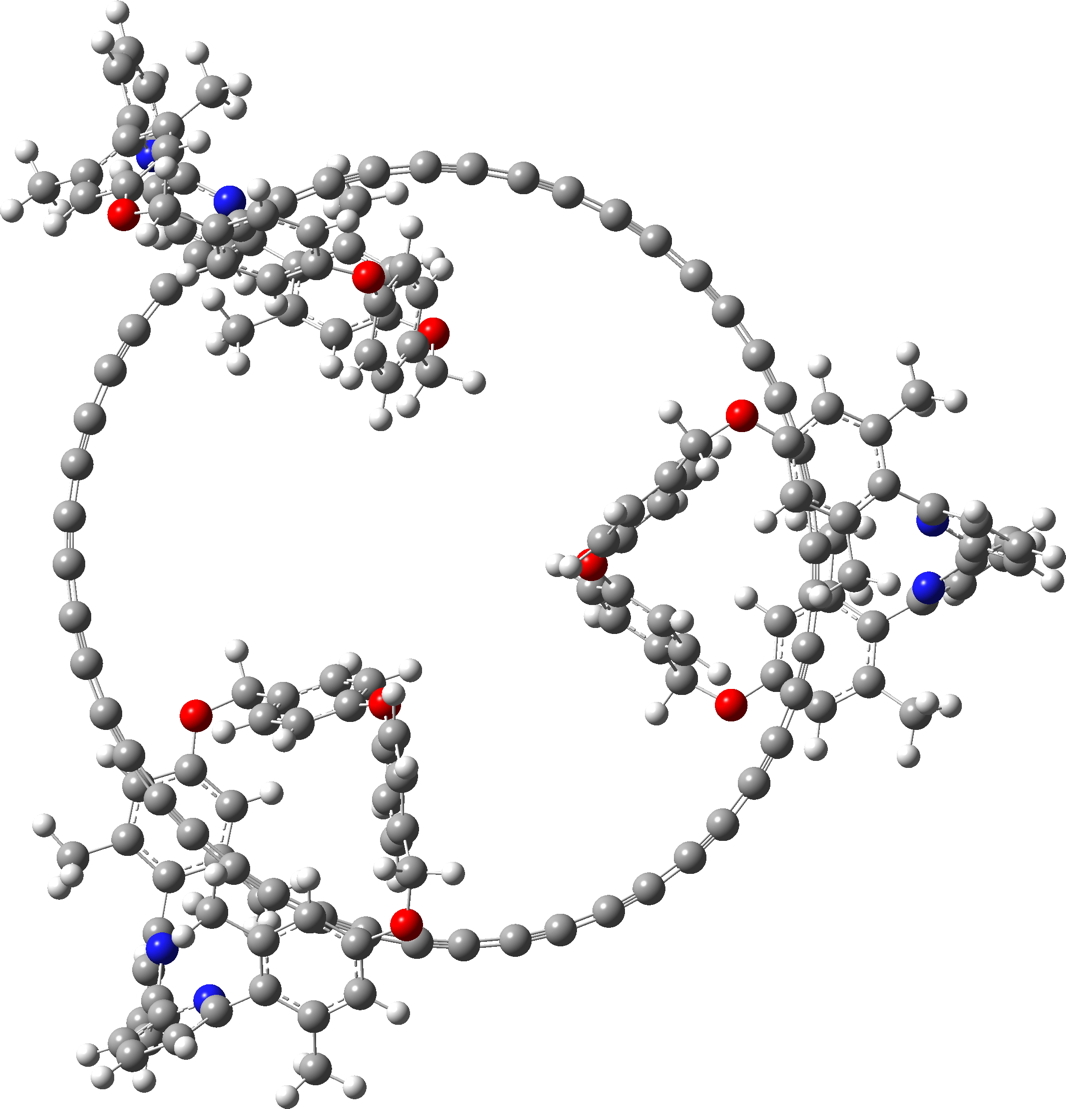

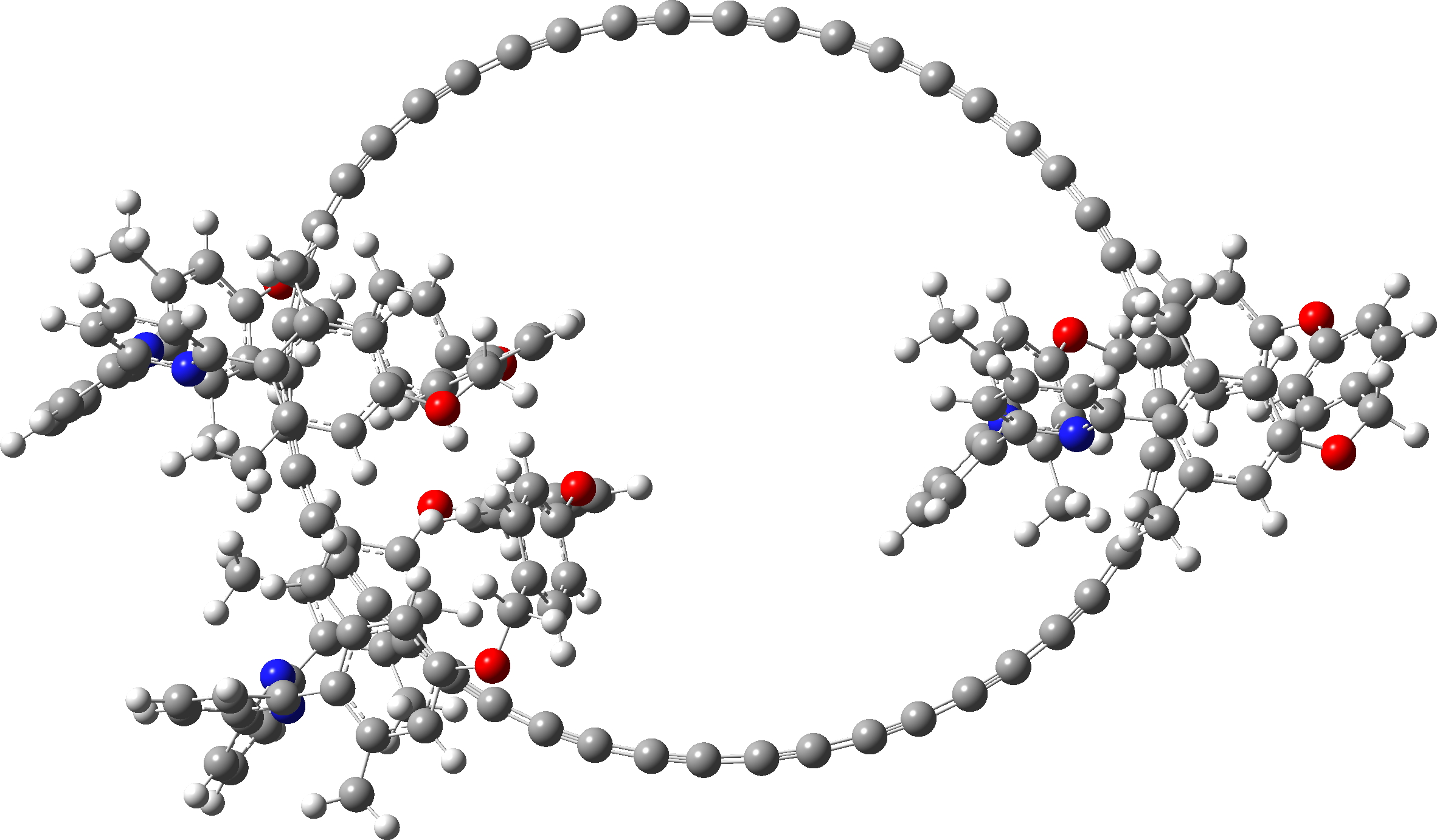

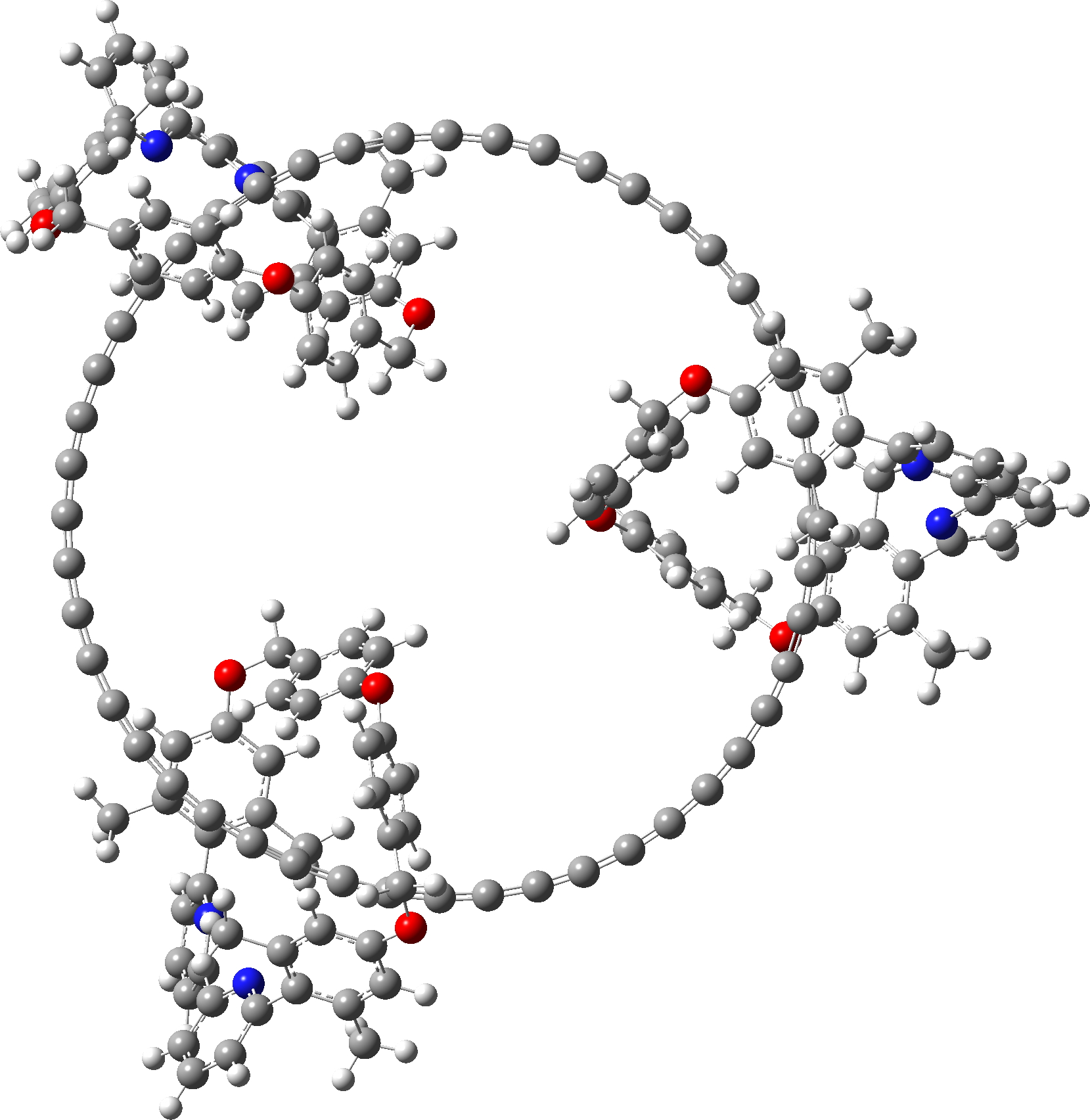

Since I did not find 3D model coordinates for the 285 atom C48.M3 in the article ESI, I generated them using the following procedures:

- Using the Chemdraw CDXML file located in the article ESI, saving as a MDL molfile and opening in Avogadro2 (direct opening of the CDXML file fails) and running Extensions/Optimise geometry. This produces an approximate 3D model using a simple molecular mechanics force field.

- These coordinates were then refined using the semi-empirical PM6 and PM7 QM methods implemented in Gaussian. The latter includes a dispersion attraction term whilst the former does not; the difference is clear to see.[4]

- This system was also finally optimised using the r2-SCAN-3c[5],[6] “Swiss army knife” thrice corrected density functional. The initial geometry was based on PM6, using the tightopt keyword, followed by a frequency calculation. Interestingly, the final geometry is closer to PM6 than to PM7. Click on the graphic above to view this 3D model.

| Table 1. |

|---|

| PM6 optimised |

|

| PM7 optimised |

|

| r2-SCAN-3c optimised |

|

The geometry of [n]-annulenes and [n]-cyclocarbons

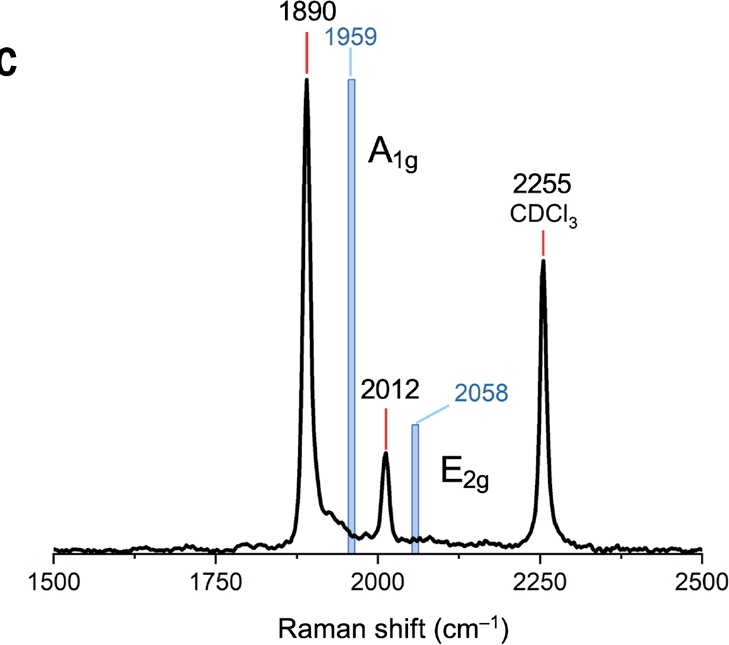

Calculating the quantum mechanical geometry of both [n]-annulenes and by association [n]-cyclocarbons is non trivial.[7],[8] Many DFT functionals for example tend to over-estimate the degree of C-C bond length alternation around the ring.[9] Recognising this, the authors of this article[1] calibrated their own adjustment to the veritable CAM-B3LYP functional against a redetermined crystal structure of [18]-annulene[10],[11],[8] calling the resulting functional OX B3LYP30[12] It was specifically optimized for extended conjugated systems by including 30% short-range exact HF exchange.[8] Significantly, [18]-annulene is an example of a 4n+2 (n = 4) cyclo-aromatic molecule for which significantly less bond alternation (if any) is expected, compared to so-called 4n-class antiaromatic molecules (e.g. cyclobutadiene (n=1)[13]). The focus of this blog – C48 – is doubly anti-aromatic (n=12), once in the σ- and then the π-frameworks and so its bonds would certainly be expected to alternate in length. This alternation directly results in the Raman activity observed in the C-C stretching regions (see Figure 4c in the article[1] and reproduced in Figure 1a below).

Here I also explore the recent r2-SCAN-3c functional,[5],[6] which importantly has NOT been adjusted, re-parametrised or scaled to achieve a particular result for these molecules and which – unlike the OX B3LYP30 method – also includes dispersion corrections.‡ Included in the table below are not only results for [18]-annulene and cyclo[48]carbon but two types of variation on the latter to test the scope of the functionals. The first was to include charged versions of C48, which reduce the electron count by either 4 (changing both the π- and σ- electron manifolds to a 4n+2 count) or by ±2 (changing just one of the manifolds to 4n+2). Also included are C14, C18, C46 (n=11; 4n+2 =46), C50 (n=12; 4n+2 =50), C58 (n=14, 4N+2=58), C62 (n=15, 4N+2=62) and C98 (n=24; 4n+2 = 98) which are all aromatic rings for which bond alternation should be much smaller, if it occurs at all. C60 is included as a larger 4n anti-aromatic molecule. It also proved possible to model the geometry of the full C48M3 catenane system as shown above using r2-SCAN-3c. FAIR data for the present calculations are published in a data repository.[14].

| Entry | System | Δra OX B3LYP30 [15] |

Δra r2-SCAN-3c [16] |

ΔG C2e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | -75.872686 | |||

| 1 | C14 | 0.00017 (2)[17] 0.00001 (0)[18] |

0.00002 (0) | -76.124925 (+6.32) |

| 2 | C18[2] | 0.00000 (2)[19] 0.06345 (0)[20] |

0.00000 (0) | -76.129778 (+3.28) |

| 3 | C18H18 | 0.0166 (0)[21] | 0.0178 (0) 0.0165[10] 0.0192[11] |

– |

| 4 | C46 | 0.11003 (0)[22] | 0.00005 (0) | -76.135596 (-0.37) |

| 5 | C484+ | 0.06892[23],[24] | 0.00005 (0) | -76.078196 |

| 6 | C482+ | 0.07459 (0)[25] | 0.03059 (0) | -76.112352 |

| 7 | C48 | 0.11087b[26] | 0.05781c (0) | -76.135003 (0.0) |

| 8 | C48 (chloroform) | 0.11087[27],[28] | 0.05810 (0) | -76.135020 |

| 9 | C48M3 | n/a | 0.05666 (in) 0.05676 (out)d | – |

| 10 | C482- | 0.07077 (0)[29] | 0.02895 (0) | -76.144764 |

| 11 | C50 | 0.00006 (2)[30] 0.00011 (1)[31], 0.11021 (0) [32] | 0.00003 (0) | -76.135728 (-0.45) |

| 12 | C58 | -0.00001 (1),[33] 0.11022 (0)[34] |

0.00011 (1, 178i),0.01159 (0) | -76.135900 (-0.56) |

| 13 | C60 | 0.11068 (0)[35] | 0.05300 (0) | -76.135547 (-0.34) |

| 14 | C62 | 0.11020 (0)[36] | 0.0001 (1, 373i) 0.02145 (0) | -76.135966 (-0.60) |

| 15 | C98 | 0.11035 (0) [37] | 0.04035 (0) | -76.135986 (-0.61) |

|

|

||||

| 16 | C49 | 0.09494 (0) [38] | 0.010050 (0) | – |

| 17 | C51 | 0.10230 (0) [39] | 0.000110 (0) | – |

| 18 | C54 | 0.11032 (0) [40] | 0.00002 (0) | -76.13583873 |

aNumber of negative force constants at this geometry in parentheses. b Raman Activity 2088, 2192 (expt 1890 A1g, 2012 E2g cm-1) cRaman Activity 1752, 1993 cm-1. d Inside and outside an M ligand. Raman modes 1767, 2013 cm-1. Calculating the intensity of these modes is still in progress, whilst program issues are resolved. eFree energy, Hartree (kcal/mol) normalised to C2 vs C2 itself at the r2-SCAN-3c level.

Bond length alternation by table entry.

- For cyclo[14]carbon, the two methods differ; the OX B3LYP30 model predicts significant bond alternation.

- For cyclo[18]carbon, the two methods differ; the OX B3LYP30 model predicts significant bond alternation.

- Both DFT methods however closely reproduce the bond length alternation in [18]annulene.

- Cyclo[46]carbon is formally 4n+2 aromatic (n=11) in both σ and π manifolds and a clear difference in bond length alternation between the two DFT methods emerges, with OX B3LYP30 predicting strong alternation and r2-SCAN-3c none.

- As with 2, entry 3 is also a 4n+2 aromatic (n=11) and again OX B3LYP30 predicts (weaker) alternation and again r2-SCAN-3c none.

- The dication has a mixed 4n+2/4n system. The same is true of entry 10.

- For the key entry 5, a 4n antiaromatic system, OX B3LYP30 predicts twice the bond alternation of r2-SCAN-3c. More surprisingly, the degree of alternation for OX B3LYP30 for this antiaromatic system is almost identical to that for eg entries 2, 9 and 10, all 4n+2 aromatic. So This functional is not responding to the 4n+2/4n rule in the normal bond length sense.

- The original calculations were done for the gas phase. Including eg chloroform as a continuum solvent has no effect on the OX B3LYP30, and a very minor effect with r2-SCAN-3c in slightly increasing the alternation.

- This is the full system, with three enclosing groups M. These have a small effect using r2-SCAN-3c, in very slightly decreasing the bond alternation depending on whether the carbon chain is enclosed by the ligand M or not.

- This is the two-carbon homologue of C48, and conforms to the 4n+2 rule. Again r2-SCAN-3c predicts no alternation (and indeed no Raman activity), whilst OX B3LYP30 again predicts a strangely invariant value of ~0.11Å.

- This 4n+2 electron molecule has one particular point of interest. Whilst the OX B3LYP30 method sticks to its standard bond length variation of Δr ~0.11Å, r2-SCAN-3c starts to depart from its previous prediction of no alternation for 4n+2 systems. One -ve force constant corresponds to an imaginary (Kekule type[3]) mode of 177i cm-1 and a geometric distortion along this mode now leads to a small bond alternation of 0.0116Å. This is particularly exciting since it has long been thought that given a large enough ring, bond alternation will start to manifest. Perhaps for r2-SCAN-3c the onset of such an effect is around 58 carbons? Previous estimates of this transition have been rather lower (~30).[41]

- This entry is included partially because of the fame of the C60 fullerene allotrope (which has a very different structure). As a cyclocarbon it is again 4n antiaromatic. Both methods predict bond alternation, albeit that the value for OX B3LYP30 is twice that of r2-SCAN-3c.

- This continues the trend first seen with entry 12; r2-SCAN-3c showing a doubling in the bond length alternation of a 4n+2 system.

- With this size ring, the bond alternation of this 4n+2 system is beginning to approach the value for a 4n system, and hence the aromatic/antiaromatic distinction is beginning to vanish.

To summarise, the entries shown in red above correspond to 4n+2 aromatic systems for which OX B3LYP30 predicts an almost constant bond alternation of ~0.011Å whereas for the same system using r2-SCAN-3c, the bond alternation is essentially zero (green). The entries marked with orange are 4n+2 aromatic for which the onset of intrinsic bond variation may have started.

Raman Activity.

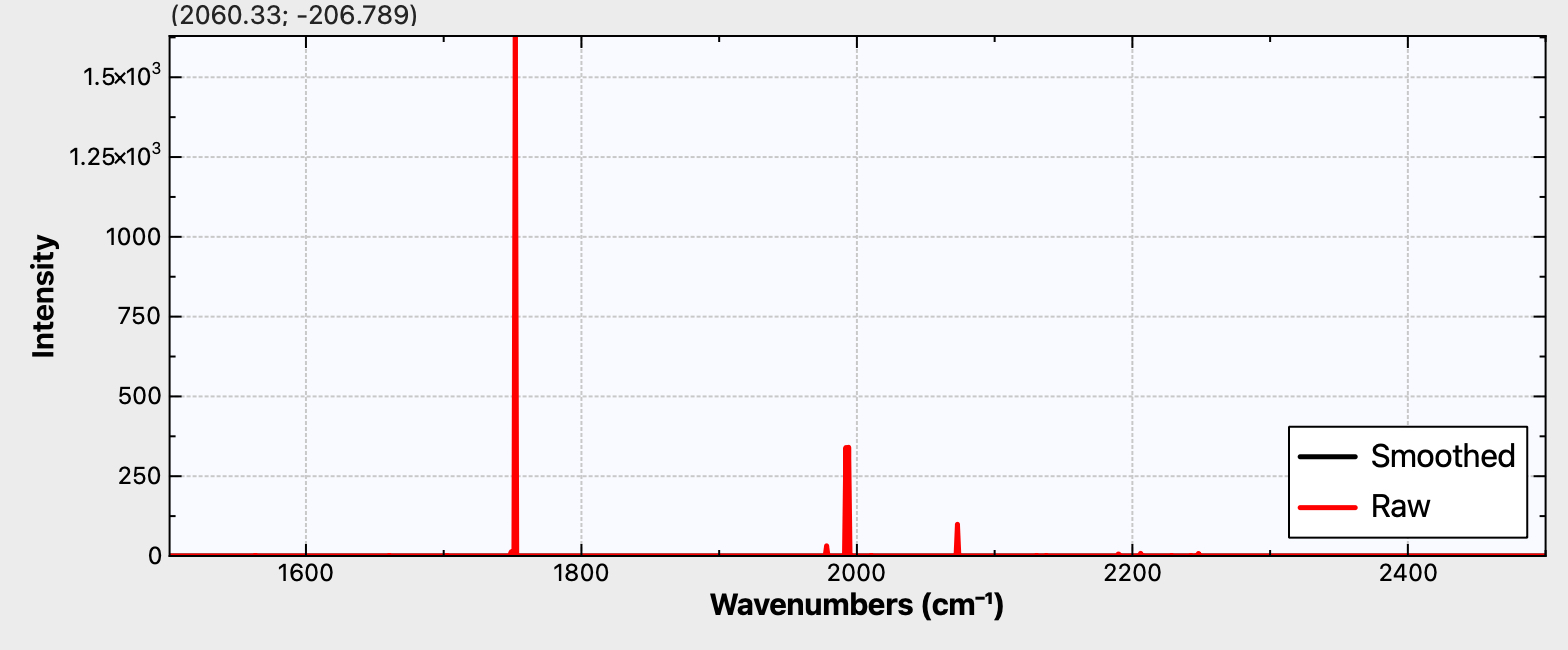

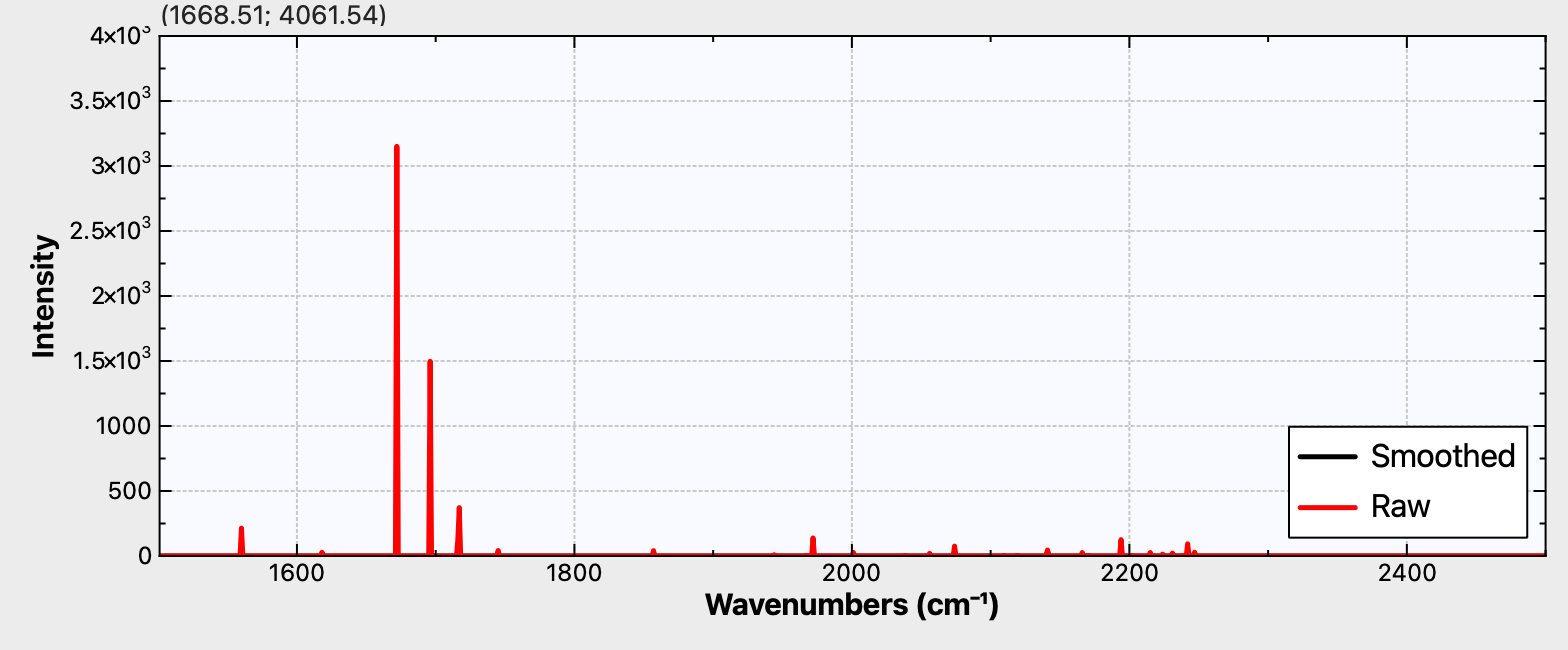

For C48M3, the measured activity as shown in figure 4c[1] is reproduced below (Figure 1a). Two modes are active, the A1g mode (the “kekule vibration“) and a less intense E2g mode. The OX B3LYP30 functional appears to reproduce this, with the values quoted in this figure (A1g 1959 and E2g 2058 cm-1 derived from scaling the OX B3LYP30 calculated values of 2088 and 2192 cm-1 reported in the supporting information data file by 0.9386). The r2-SCAN-3c functional likewise predicts the A1g mode (1752 cm-1, unscaled) to be more intense than E2g 1993 cm-1 (Figure 1b). Before we conclude which method is achieving the better result, the effect induced by the surrounding M3 ligands should be taken into account. We see in the table that the predicted CC bond length variation in the unmasked ring (0.0578) is slightly decreased in C48M3 to 0.0567, as are the bond lengths themselves (1.24839Å gas; 1.24699Å M3). The Raman modes in C48M3 (1767, 2013 cm-1) are calculated a little higher in wavenumber than C48 itself, but final assignment will depend on calculation of the Raman intensity, which is ongoing (see comment below).

Figure 1a. Observed Raman activity for C48

Figure 1b. Calculated r2-SCAN-3c Raman activity for C48

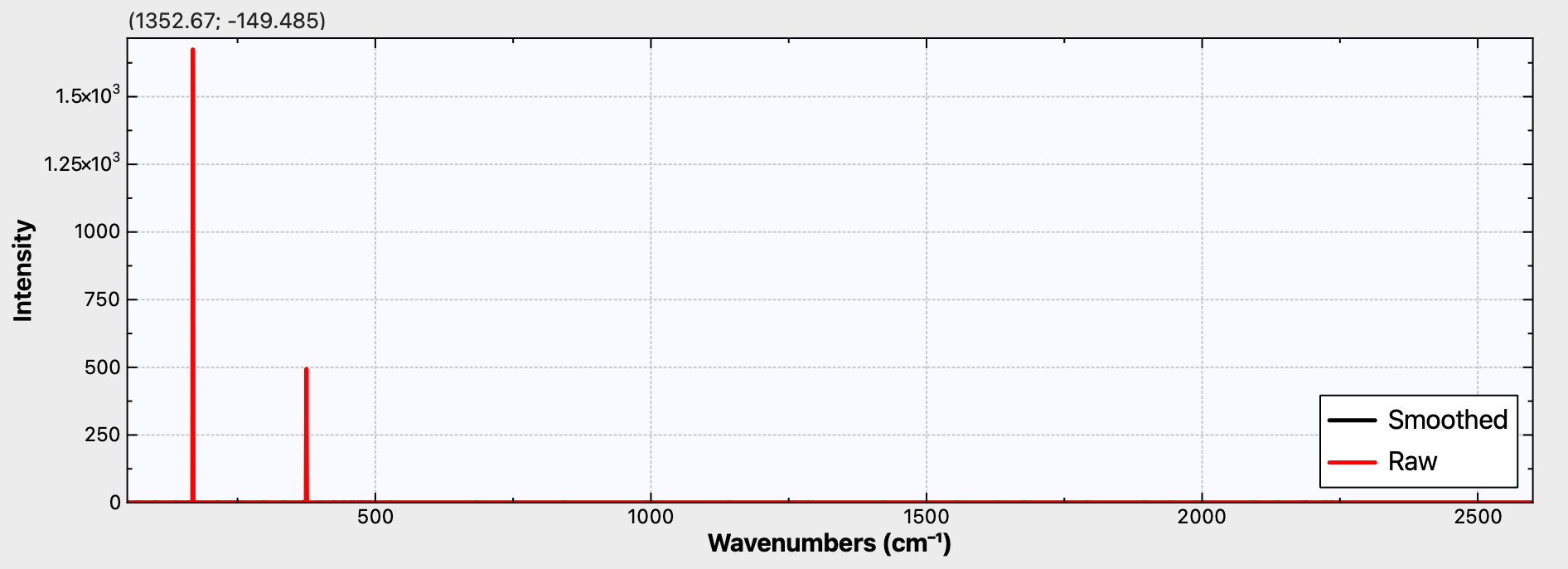

Figure 1c. Calculated r2-SCAN-3c Raman activity for C50

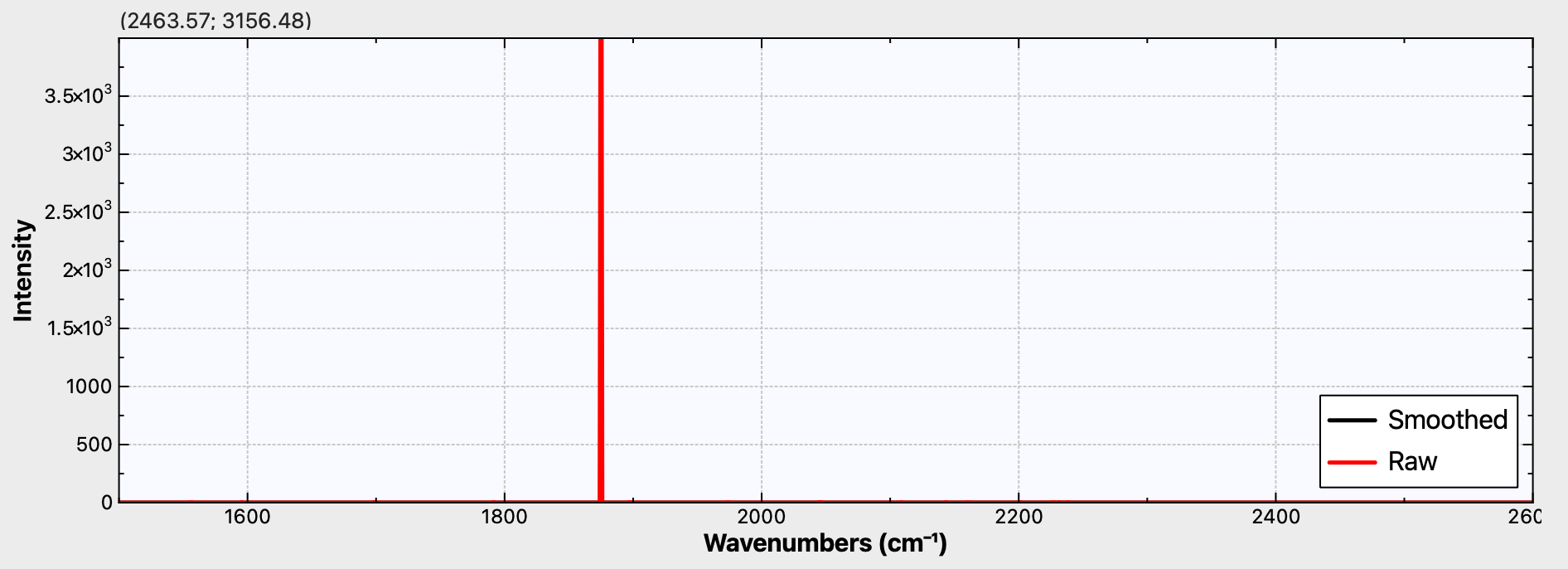

Figure 1d. Calculated r2-SCAN-3c Raman activity for C58

Figure 1d. Calculated r2-SCAN-3c Raman activity for C58

Figure 1e. Calculated r2-SCAN-3c Raman activity for C98

Conclusions

The synthesis of cyclo[48]carbon and its stabilized derivative C48.M3 has provided a nice opportunity to investigate the strange phenomenon of bond alternation in cyclic carbon systems, coupled with experimental measurements of Raman activity and comparison with calculation. The recent constrained♥ functional r2-SCAN-3c and perhaps similar ones such as the forthcoming COACH[42] might prove useful in modelling the properties of these unusual compounds of carbon. The r2-SCAN-3c method also suggests that the 4n+2 series cyclocarbons are slightly more stable in terms of free energy than the 4n series.

It is to be hoped that a 4n+2 series example can be synthesized. For one such, e.g. cyclo[58]carbon or especially cyclo[98]carbon, Raman activity is again predicted (Figure 1d,e), whilst for the smaller cyclo[50]carbon (Figure 1c), this activity is predicted absent. Providing a test of this behaviour might provide a motivation for the synthesis of these larger systems!

‡Thus the dispersion stabilisation for C48 is -11.5 kcal/mol. ♥Constraints are exact conditions that an ideal (DFT) functional should have. Though the exact density functional is not known, researchers have discovered analytical properties of such a functional.[43]. The functional SCAN[44] satisfies the 17 derived constraints; many earlier functionals satisfy less than 6 or fewer.

This post has DOI: 10.59350/g4309-gv109

References

- Y. Gao, P. Gupta, I. Rončević, C. Mycroft, P.J. Gates, A.W. Parker, and H.L. Anderson, "Solution-phase stabilization of a cyclocarbon by catenane formation", Science, vol. 389, pp. 708-710, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.ady6054

- K. Kaiser, L.M. Scriven, F. Schulz, P. Gawel, L. Gross, and H.L. Anderson, "An sp-hybridized molecular carbon allotrope, cyclo[18]carbon", Science, vol. 365, pp. 1299-1301, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay1914

- H. Rzepa, "Cyclo[18]carbon: The Kekulé vibration calculated and hence a mystery!", 2019. https://doi.org/10.59350/jdy16-7rv58

- H. Rzepa, "Molecules of the year -2022. A closer look at the Megalo-Cavitands.", 2022. https://doi.org/10.59350/x9m30-5aa79

- S. Grimme, A. Hansen, S. Ehlert, and J. Mewes, "r2SCAN-3c: A “Swiss army knife” composite electronic-structure method", The Journal of Chemical Physics, vol. 154, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0040021

- F. Neese, F. Wennmohs, U. Becker, and C. Riplinger, "The ORCA quantum chemistry program package", The Journal of Chemical Physics, vol. 152, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0004608

- H. Rzepa, "Bond length alternation (BLA) in large conjugated rings: an (anti-aromatic) update.", 2019. https://doi.org/10.59350/nnctg-v6535

- R.A. King, P.R. Schreiner, and T.D. Crawford, "Structure of [18]Annulene Revisited: Challenges for Computing Benzenoid Systems", The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, vol. 128, pp. 1098-1108, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.3c07797

- I. Casademont-Reig, E. Ramos-Cordoba, M. Torrent-Sucarrat, and E. Matito, "How do the Hückel and Baird Rules Fade away in Annulenes?", Molecules, vol. 25, pp. 711, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25030711

- Stawski, Wojciech., Zhu, Yikun., Rončević, Igor., Wei, Zheng., Petrukhina, Marina A.., and Anderson, Harry L.., "CCDC 2293565: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination", 2024. https://doi.org/10.5517/ccdc.csd.cc2gzmz2

- Lungerich, Dominik., Nizovtsev, Alexey V.., Heinemann, Frank W.., Hampel, Frank., Meyer, Karsten., Majetich, George., Schleyer, Paul v. R.., and Jux, Norbert., "CCDC 1452788: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination", 2016. https://doi.org/10.5517/cc1krr46

- M. Vitek, J. Deng, H.L. Anderson, and I. Rončević, "Global Aromatic Ring Currents in Neutral Porphyrin Nanobelts", ACS Nano, vol. 19, pp. 1405-1411, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.4c14100

- H. Rzepa, "Stable "unstable" molecules: a crystallographic survey of cyclobutadienes and cyclo-octatetraenes.", 2017. https://doi.org/10.59350/7m9dm-an754

- H. Rzepa, "Molecules of the year 2025: Cyclo[48]carbon - bond alternation and Raman Activity Spectrum.", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15614

- H. Rzepa, "Molecules of the year 2025: Cyclo[48]carbon – bond alternation and Raman Activity Spectrum. Gaussian calculations", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15617

- H. Rzepa, "Molecules of the year 2025: Cyclo[48]carbon – bond alternation and Raman Activity Spectrum. ORCA 6.1 calculations", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15615

- H. Rzepa, "C14 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100) 2 -ve FC", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15640

- H. Rzepa, "C14 2-ve FC => 0 -ve", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15641

- H. Rzepa, "C18 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100) 2 -ve FC", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15619

- H. Rzepa, "C18 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100) 2 -ve => 0 -ve", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15620

- H. Rzepa, "C18H18 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100)", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15625

- H. Rzepa, "C46 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100)", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15626

- H. Rzepa, "C48 +4 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100) 2 -ve", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15627

- H. Rzepa, "C48 +4 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100) 3 -ve => 0 -ve", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15628

- H. Rzepa, "C48 +2 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100)", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15629

- H. Rzepa, "C48 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100)", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15630

- H. Rzepa, "C48 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100) chloroform", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15631

- H. Rzepa, "C48 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100) NMR 13C = 85.1 ppm", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15622

- H. Rzepa, "C48 -2 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100)", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15632

- H. Rzepa, "C50 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100) (2 -ve FC)", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15635

- H. Rzepa, "C50 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100) (1 -ve FC)", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15633

- H. Rzepa, "C50 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100) (0 -ve FC)", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15637

- H. Rzepa, "C58 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100) 1 -ve", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15636

- H. Rzepa, "C58 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100) 0 -ve", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15634

- H. Rzepa, "C60 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100) 0 -ve fre", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15624

- H. Rzepa, "C62 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100) 0 -ve fre", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15618

- H. Rzepa, "C98 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100) (0 -ve FC)", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15638

- H. Rzepa, "C49 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100)", 2026. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15671

- H. Rzepa, "C51 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100)", 2026. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15670

- H. Rzepa, "C54 OX B3LYP30 (10.1021/acsnano.4c14100)", 2026. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15669

- C.H. Choi, and M. Kertesz, "Bond length alternation and aromaticity in large annulenes", The Journal of Chemical Physics, vol. 108, pp. 6681-6688, 1998. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.476083

- H. Rzepa, "WATOC 2025 report – extending the limits of computation (accuracy).", 2025. https://doi.org/10.59350/rzepa.28931

- S. Helal, Z. Tao, C. Rubio-González, F. Gygi, and A.V. Thakur, "Towards Verifying Exact Conditions for Implementations of Density Functional Approximations", SC24-W: Workshops of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, pp. 160-169, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1109/scw63240.2024.00027

- J.W. Furness, A.D. Kaplan, J. Ning, J.P. Perdew, and J. Sun, "Accurate and Numerically Efficient r<sup>2</sup>SCAN Meta-Generalized Gradient Approximation", The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, vol. 11, pp. 8208-8215, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c02405

I have added entries 16-18 to the table. This includes C54, which is potentially amenable to synthesis by the same method as used in the article. This confirms that bond alternation only starts with C58. It also includes two odd-number entries, C49 and C51, which are are half aromatic and half antiaromatic. C49 shows a small degree of bond alternation using the r2scan-3C method and C51 none. The origins of this behaviour would need further investigation.

I attach here an animation of mode 42 for C54 calculated using r2SCAN-3c. This is the largest cyclocarbon for which the so-called Kekule mode is still positive (ν 264 cm-1). This mode contracts 24 pairs of carbon and elongates the other 24 pairs to produce a long-short motif around the ring. The same mode in benzene has a value of ~1309 cm-1 (DOI: 10.59350/tm2r5-cyh62) and also this earlier commentary for C18 for which the calculated Kekule mode is 1265 (DOI: 10.59350/jdy16-7rv58), whilst C14 is 1469 cm-1.

The same vibration in C58 has a calculated value of 178i cm-1 (a transition state with one imaginary mode).

So this mode changes by 442 cm-1 for an addition of four extra carbon atoms; the effect seems quite abrupt.

I noted in the post that the calculated Raman activity intensities of the complex C48M3 (1767, 2013 cm-1) using r2SCAN-3c were not reported at the time. In ORCA V 6.0, these can only be calculated using numerical second derivatives, and attempts to do so produced a program error. With the recently released ORCA 6.1.2, analytical second derivatives are now available and this has enabled these intensities to be reported, as seen below.