In this follow-up to the previous post, I will try to address the question what is the nature of the bonds in penta-coordinate carbon?

Posts Tagged ‘Interesting chemistry’

Capturing penta-coordinate carbon! (Part 2).

Wednesday, September 23rd, 2009Capturing penta-coordinate carbon! (Part 1).

Tuesday, September 22nd, 2009The bimolecular nucleophilic substitution reaction at saturated carbon is an icon of organic chemistry, and is better known by its mechanistic label, SN2. It is normally a slow reaction, with half lives often measured in hours. This implies a significant barrier to reaction (~15-20 kcal/mol) for the transition state, shown below (X is normally both a good nucleophile and a good nucleofuge/leaving group, such as halide, cyanide, etc. Y can have a wide variety of forms).

Spotting the unexpected: Anomeric effects

Friday, September 18th, 2009Chemistry can be very focussed nowadays. This especially applies to target-driven synthesis, where the objective is to make a specified molecule, in perhaps as an original manner as possible. A welcome, but not always essential aspect of such syntheses is the discovery of new chemistry. In this blog, I will suggest that the focus on the target can mean that interesting chemistry can get over-looked (or if observed, not fully exploited in subsequent publications). Taking a synthesis-oriented publication at (almost) random entitled Synthesis of 1-Oxadecalins from Anisole Promoted by Tungsten (DOI: 10.1021/ja803605m) which appeared in 2008, the following molecule appears as one of the (many) intermediates.

Towards the ultimate bond!

Monday, August 24th, 2009

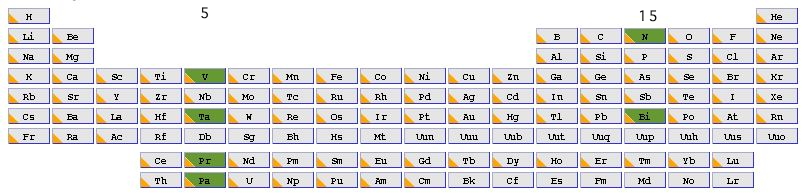

The 100th anniversary of G. N. Lewis’ famous electron pair theory of bonding is rapidly approaching in 2016 (DOI: 10.1021/ja02261a002). He set out a theory of bond types ranging from 1-6 electrons. The strongest bond recognized by this theory was the 6-electron triple bond, a good example of which occurs in dinitrogen, N2. In terms of valence electrons, nitrogen has an atomic configuration of 2s2, 2p3. Each atom has five electrons in total, some or all of which in principle could be used for forming bonds. An exploration of this motif across the entire periodic table is presented in part one of this blog.

Nitrogen is in the main group 15, and the element at the bottom of this group is Bismuth (also with the same atomic configuration). We can then move to the corresponding column of the transition series, this time occupying group 5. The first examplar in this set, Vanadium has an atomic configuration of 3d3, 4s2, again five valence electrons, but now utilizing the d- rather than the p-shell of valence atomic orbitals (AOs). The final forage across the period table would land us with Pr and Pa, which occupy the lanthanide and actinide series respectively, and which have atomic configurations of 4f3, 6s2 and 5f2, 6d1 and 7s2 respectively. You can now see the theme developing; how does the bonding develop between two atoms that between them have ten valence electrons occupying molecular orbitals constructed from s, and then either p, d or f atomic orbitals. The next in that series, g atomic orbitals, are thought unlikely to have any chemical significance in the presently known periodic table.

Molecular toys: Tetrahedral cavities

Saturday, July 4th, 2009

An earlier post described how a (spherical) halide anion fitted snugly into a cavity generated by the simple molecule propanone, itself assembled by sodium cations coordinating to the oxygen. A recent elaboration of this theme, reminiscent of the children’s toys where objects have to be fitted into the only cavity that matches their shape, Nitschke and co-workers report the creation of a molecule with a tetrahedral rather than a spherical cavity (DOI: 10.1126/science.1175313 ), into which another but much smaller tetrahedral molecule is fitted. The small molecule is P4, in which each of the three valencies of the P atom is directed to a corner of the tetrahedron. The large molecule comprises four Fe atoms. These are each octahedrally coordinated with six ligand sites, three of which mimic the P atoms in also being directed towards the remaining three vertices of a tetrahedron.

Longer is stronger.

Saturday, June 6th, 2009The iconic diagram below represents a cornerstone of organic chemistry. Generations of chemists have learnt early on in their studies of the subject that these two representations of where the electron pairs in benzene might be located (formally called electronic resonance or valence bond forms) each contribute ~50% to the overall wavefunction, and that the real electronic description is in effect an average of these two (that is the implied meaning of the double headed arrow). This means that the six C-C bonds in benzene must all be of equal length. The diagrams, everyone knows, do not mean that benzene has three short and three long C-C bonds.

The mystery of the Finkelstein reaction

Saturday, May 16th, 2009This story starts with an organic chemistry tutorial, when a student asked for clarification of the Finkelstein reaction. This is a simple SN2 type displacement of an alkyl chloride or bromide, using sodium iodide in acetone solution, and resulting in an alkyl iodide. What was the driving force for this reaction he asked? It seemed as if the relatively strong carbon-chlorine bond was being replaced with a rather weaker carbon-iodine bond. But its difficult to compare bond strengths of discrete covalent molecules with energies of ionic lattices. Was a simple explanation even possible?

The Chirality of Lemniscular Octaphyrins

Tuesday, April 28th, 2009In the previous post, it was noted that Möbius annulenes are intrinsically chiral, and should therefore in principle be capable of resolution into enantiomers. The synthesis of such an annulene by Herges and co-workers was a racemic one; no attempt was reported at any resolution into such enantiomers. Here theory can help, since calculating the optical rotation [α]D is nowadays a relatively reliable process for rigid molecules. The rotation (in °) calculated for that Möbius annulene was relatively large compared to that normally measured for most small molecules.

The chirality of Möbius annulenes

Wednesday, April 22nd, 2009Much like climbing Mt. Everest because its there, some hypothetical molecules are just too tantalizing for chemists to resist attempting a synthesis. Thus in 1964, Edgar Heilbronner speculated on whether a conjugated annulene ring might be twistable into a Möbius strip. It was essentially a fun thing to try to do, rather than the effort being based on some anticipated (and useful) property it might have. If you read the original article (rumour has it the idea arose during a lunchtime conversation, and the manuscript was completed by the next day), you will notice one aspect of these molecules that is curious by its absence. There is no mention (10.1016/S0040-4039(01)89474-0) that such Möbius systems will be chiral. By their nature, they have only axes of symmetry, and no planes of symmetry, and such molecules therefore cannot be superimposed upon their mirror image; as is required of a chiral system (for a discussion of the origins and etymology of the term, see 10.1002/chir.20699).