Scheme 1. The mechanism for intermolecular aldol condensation with proline as a chiral auxilliary (green), and key stereocentres created by bond formation between the C=C and the carbonyl (red bond).

Abstract. The ten year old Houk-List model for rationalising stereoselective organocatalysis of the intermolecular aldol condensation is revisited using a variety of computational techniques which have been introduced or improved since the original study. Even for such a relatively small system, the role of dispersion interactions is shown to be crucial, along with the use of basis sets where the superposition errors are low. An NCI (non-covalent-analysis) of the transition states shows good correlation with the relative computed free energies, which provides a new analytical technique to be used in modelling stereoselectivity. Alternative mechanisms, such as proton-relays involving a water molecule or the Hajos-Parrish alternative, are shown to be higher in energy.

The promotion of a wide range of organic synthetic reactions using new generations of so-called organocatalysts (metal free systems) is highly topical. So too is the increasing adoption of computational modelling to chart the most probable mechanistic pathway and, in particular, to establish the factors responsible for reactivity and selectivity, particularly stereoselectivity.1 In this regard, one particular report in 20032 of computational investigation of the proline-mediated asymmetric intermolecular aldol reactions (Scheme 1) has achieved the rare distinction of having the key transition state model being named after the two principle authors; Houk and List. This computational model has informally become known as the gold standard for such investigations, since it set out the procedures for comparing computational modelling with experimental results for organocatalysed reactions, and outlines a methodology for predicting the stereoselectivity for new organocatalysed reactions.

Scheme 1. The mechanism for intermolecular aldol condensation with proline as a chiral auxilliary (green), and key stereocentres created by bond formation between the C=C and the carbonyl (red bond).

A one-proline mechanism based on enamine activation, the Houk-List transition state model involves the stereogenic carbon-carbon bond formation step of the catalytic cycle, when the catalytically active enamine attacks an electrophile. The carboxylic acid of proline plays a central role in this model, directing the electrophile to the Re face of the enamine. The enamine can be anti or syn, relative to the acid, and the electrophile can offer two prochiral faces for attack, Re or Si, resulting in four different stereochemical outcomes (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. The stereochemical possibilities for the asymmetric aldol condensation. Cahn-Ingold-Prelog conventions are shown for R=Ph.

Through extensive computational studies,2-6 Houk and Bahmanyar suggest that the energy differences between these transition state, and so the origin and degree of stereoselectivity displayed by the reaction, depends on two critical structural elements: the relative degree to which each transition state can adopt a planar enamine, and the degree of electrostatic stabilisation provided to the forming alkoxide. A planar enamine allows for the greatest possible nucleophilicity of the terminal olefin while also reducing the geometric distortion experienced by the forming iminium. The proton transfer, from the carboxylic acid to the forming alkoxide, was determined to provide the majority of the electrostatic stabilisation and is key to the Houk-List transition state.2,7 A smaller, yet important, stabilising contribution also results from NCHᵟ+∙∙∙Oᵟ- interactions from the pyrrolidine ring.8

The stereoisomer for which these key elements were most favourable was calculated as that noted (S,R), for R = Ph, iPr. This prediction was then verified by experimental study, where the (S,R) stereoisomer was observed formed in 60% enantiomeric excess (R=Ph) or 96% (R=iPr). The challenge of computational methods then is to establish a transition state model in which this behaviour can be rationalised and so used to predict the outcome of further reaction variations. Any success of such models can then be used build confidence for diversification to new reactions and mechanisms.

Indeed, the Houk-List model has enjoyed a high degree of success in application to the prediction of the stereochemical outcomes of a number of proline mediated reactions: from the inter-2 and intramolecular6 aldol, Mannich,4 α-alkylation,9 and Michael reactions,10 among several others,1 to the correct prediction of the outcome of reactions mediated by analogues of proline.7,8,11-13 However, despite the apparently excellent comparison made between computational and experimental selectivities, for which this research became widely known, two significant issues have come to light regarding the details of the proline-cyclohexanone-benzaldehyde system. Houk has since disclosed that calculations carried out subsequent to publication, in which a greater volume of conformational space was investigated, suggest that lower energy structures of the transition states exist;1,14 potentially altering the predicted selectivity of the reaction. In addition, repetition of the experimental results by List found product selectivities to vary, with the reaction found to be extremely sensitive to both water content and temperature. As such, despite the success of the Houk-List model as a concept, the reportedly excellent agreement between computational and experimental results appears to be coincidental.

The ten years that have elapsed since the original report has also seen many incremental and sometimes dramatic improvements to the computational methods used, and so in the present article we re-evaluate the Houk-List model by taking advantages of these; the gold standard itself must evolve. A more accurate computational model in turn allows the experimental findings to be subjected to improved scrutiny, and potentially this can itself result in suggestions for further experimental tests.

Because fully substituted reacting systems can have > 20 atoms and the organocatalysts themselves are potentially large molecules, the level of theory adopted by the Houk-List model in 2003 was (as always) a pragmatic compromise between the quality of the theory and the requirement to be able to compute the model in a reasonable time (a four day batch run is a typical resource available to most). The level of theory originally selected by Houk and co-workers was B3LYP/6-31G*, and geometries, activation enthalpies and free energies (ΔG298) based on calculating the normal vibrational modes at this level were obtained for a gas phase model. To these energies (and at these geometries) various further corrections could be added, including an estimation of the solvation energy computed for a polarizable continuum model. This procedure was then applied to an exploration of the conformational space available to the system. Because this has many degrees of freedom, only the most likely conformations were explored; no exhaustive procedure was applied. So how can this approach be improved upon in 2013? We have focused on six aspects set out below.

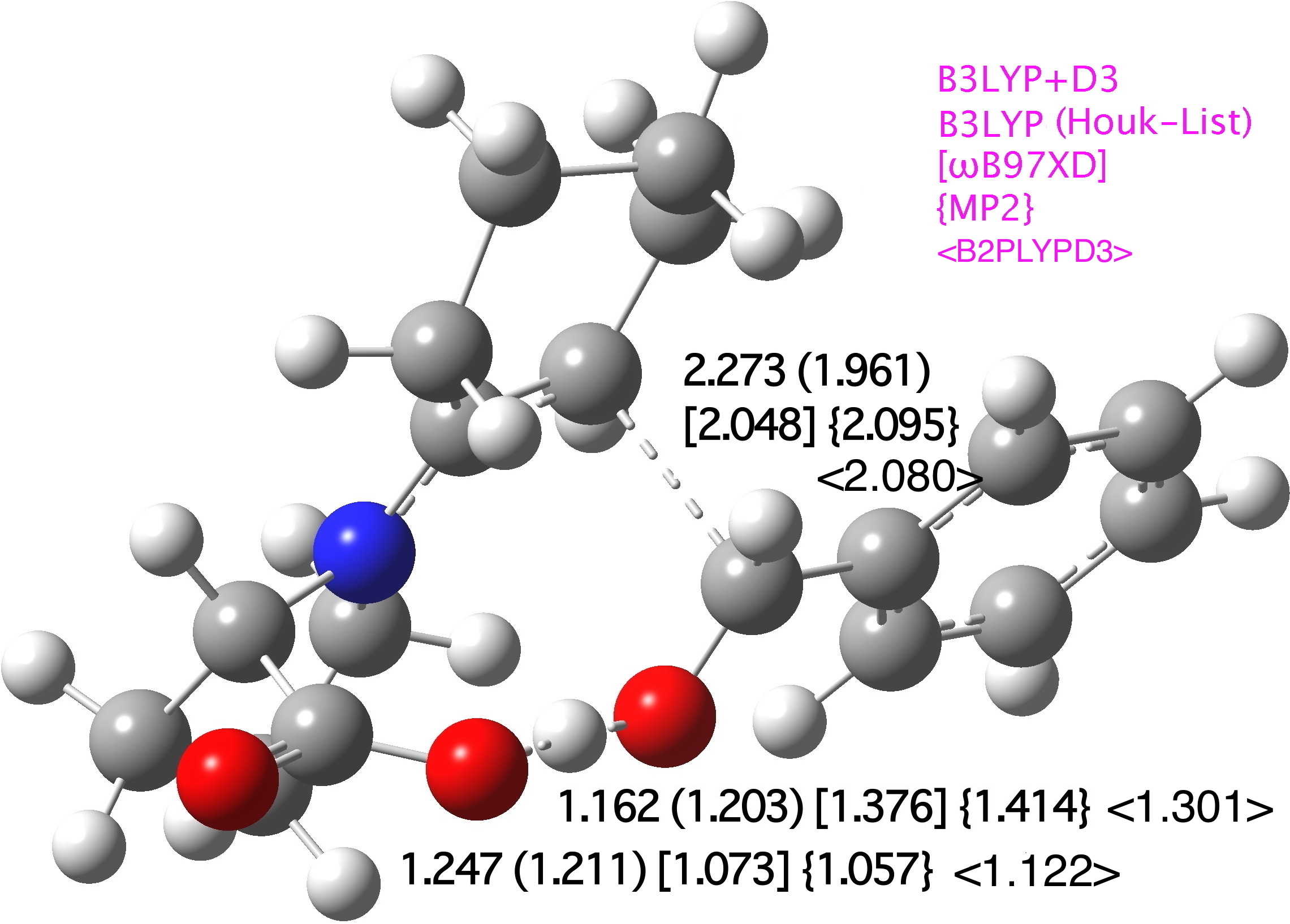

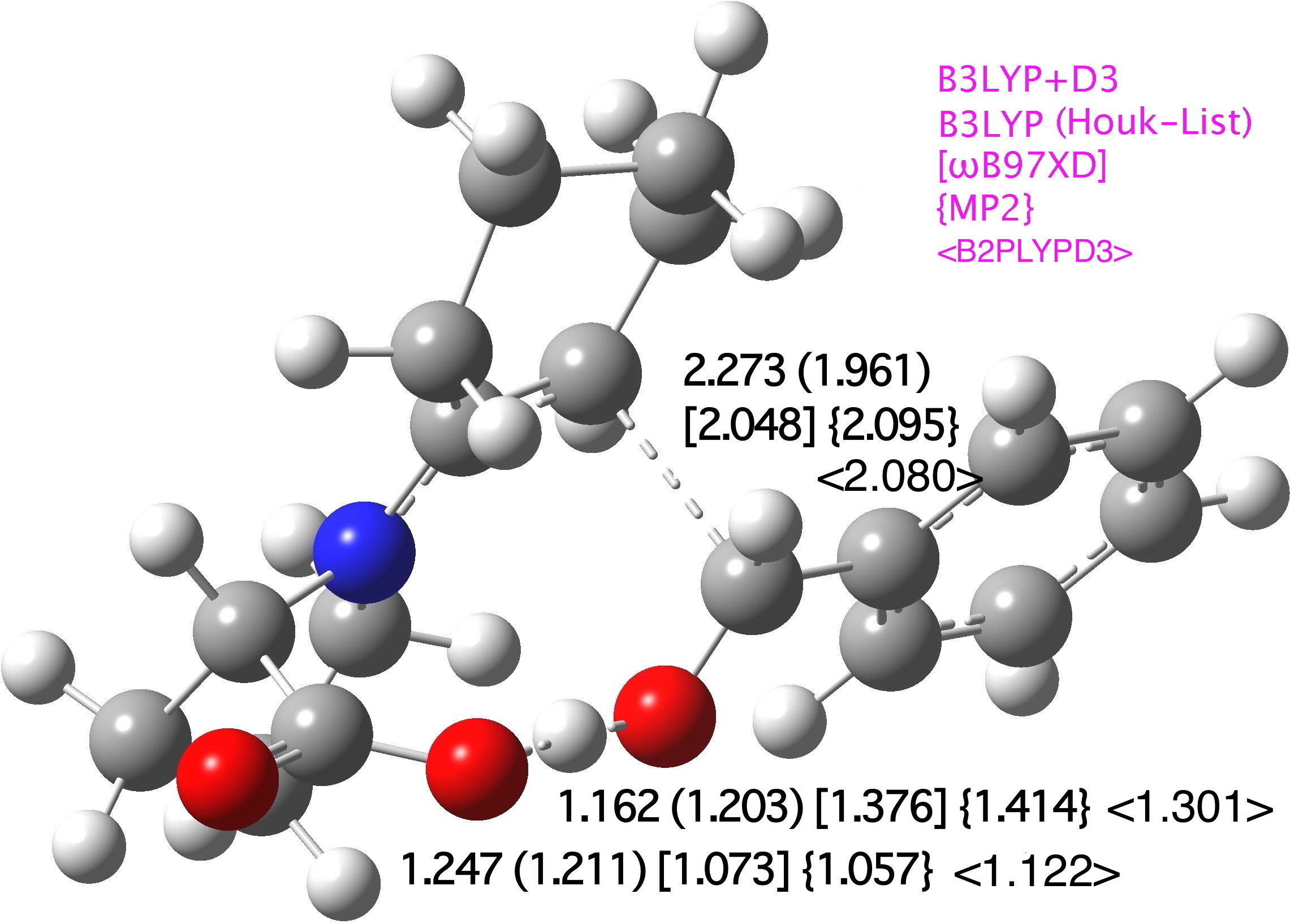

The core mechanism, as shown in Scheme 1, results in the creation of two stereogenic centres by the formation of a new C-C bond, accompanied by a key proton transfer from the carboxyl group to the oxygen of the carbonyl substrate. Our base-level theory is specified as B3LYP+D3/TZVP/SCRF=DMSO, and geometries at this level for R=Ph and R=iPr (Figure 1) reveal subtle differences in the degree of C-C bond formation and accompanying proton transfer. Larger variation is induced by a change of functional (to ωB97XD), but the latter values are similar to that obtained using the MP2/6-31G(d,p)/SCRF=DMSO approach. We note that the smaller 6-31G(d,p) basis set is the largest for which a practical MP2 calculation can be run (on a 64-processor, ultra large memory system).

The effect of including the D3-dispersion term on the B3LYP-computed geometries is not entirely insignificant; the correction changes the C-C length of the forming bond at the transition state from 2.251 to 2.273Å and the proton transfer geometry from 1.242/1.166 to 1.247/1.162Å (R=Ph). The corresponding values for R=iPr are 2.159 to 2.115 for C-C and 1.154/1.262 to 1.151/1.269Å for the proton transfer.

Figure 1. Computed selected bond lengths at B3LYP+D3/TZVP/SCRF=DMSO for (a) R=iPr in Å (original Houk-List values) (b) R=Ph (original Houk-List values) [MP2(FC)//6-31G(d,p)/SCRF=DMSO], {ωB97XD/TZVP/SCRF=CPCM}

A B3LYP+D3/TZVP/SCRF=DMSO intrinsic reaction coordinate for R=Ph and R=iPr (Figure 2) shows C-C bond formation is synchronous in both cases with proton transfer. There is no sign of what Cremer22 has referred to as a hidden intermediate, the frustrated formation of an intermediate sandwiched between C-C bond formation and proton transfer.

Figure 2. Computed intrinsic reaction coordinate at B3LYP/TZVP+D3/SCRF=DMSO, for (a) R=Ph, (b) R=iPr. The corresponding digital repository identifiers are DOI: n46 and n45

Before undertaking a stereochemical and conformational exploration of the transition state described above, we first addressed the effect that basis set quality could have on the difference in total calculated energy between two stereoisomers. The BSSE (basis set superposition error) between the anti and syn transition state geometries was estimated for three basis sets; the original Houk-List 6-31G(d), the commonly used rather larger 6-311G(d,p) basis and TZVP (using the Boys-Bernadi counterpoise method, as implemented in ORCA 2.9.1)23

These results clearly show that errors due to this effect can be of the order of 1 kcal/mol at the original 6-31G(d) level selected in 2003, are still relatively large (~0.8 kcal/mol) for the larger 6-311G(d,p) basis and only become insignificant for the TZVP basis (~0.2 kcal/mol). From these results we suggest that the TZVP is the minimum basis set quality appropriate for fidelity in stereochemical prediction; it is used for all the calculations reported here.

We next explored the relative free energies of the four stereochemical outcomes possible for the reaction (Scheme 2), for each of which there are four plausible conformational possibilities (Scheme 3). The results for R=Ph are shown in Table 2 and those for R=iPr in Table 3.

Scheme 3. The four considered conformational possibilities for the asymmetric aldol condensation.

The results are presented in the form of two tables. Table 2 contains a replication of the original Houk-List study2 using the same methods are previously reported and Table 3 an updated version using the improved methodologies discussed above. ......... tba

The results for R=Ph (Table 3) confirm the Houk-List result that the (S,R) stereoisomer is the dominant isomer formed; the nearest alternative stereoisomer is the (S,S) form, which emerges as 4.59 kcal/mol higher in free energy using B3LYP/TZVP/SCRF=DMSO, a value reduced to 2.97 kcal/mol if the dispersion energy corrected is included in the procedure. Overall, we see that inclusion of such corrections for this system decreases the predicted enantioselectivity to 98.6% ee from effectively 100%. The is nevertheless still at odds with the reported experimental value of ~60% ee. As we note in the introduction, the experimental value may however be extremely sensitive to both water content and temperature. Similar conclusions can be drawn for R=iPr (Table 3).

The maximum difference in energy between the lowest conformer of the (S,R) form and the highest energy conformer of the least stable stereoisomer (R,S) is 7.88 kcal/mol using the B3LYP+D3 functional, 7.72 kcal/mol at the ωB97XD level (which includes a 2nd generation dispersion correction) and 8.11 kcal/mol at the MP2 level using a 6-31G(d,p) basis set (it proved impractical to use the larger TZVP basis for this calculation).

Stereoselectivity is controlled by a combination of stereoelectronically-induced bond orientations and formations in the transition state, influenced by non-bonded weak interactions (NCI) within the framework. Although the balance of these latter interactions can be difficult to compute from total energies alone, it has been recently shown24 that the the computed reduced (electron) density gradients (RDG), filtered to remove the density due to covalent bonds from the analysis to leave only the weaker non-covalent interactions, can be much more effective at revealing the non-bonded interactions present and also a more realistic analysis than pure topological indices such as QTAIM.25 Such an NCI index can be obtained by contouring the RDG as isosurfaces, and colour-coding these using the appropriate eigenvalue (sign(λ2)ρ) of the density Hessian to reveal both stabilizing regions (blue for stronger hydrogen-bonded types, green for weaker van der Waals types) or destabilizing regions (strong steric clashes map to red, and weaker ones to yellow). This represents a semi-quantitative and highly visual way of analysing what is often merely described in a non-quantitative (and often intuitive) manner merely as transition state steric clashes and hydrogen bond/electrostatic attractions. Since the weaker van der Waals type dispersion attractions are very much part of such an analysis, we consider it crucial to also compute the geometry by inclusion of such terms in the Hamiltonian, as has been done here via the D3- dispersion correction.

The NCI surface (B3LYP+D3/TZVP/SCRF=DMSO, Figure 3a) for the transition state stereoismer shown in Figure 1, representing that of lowest energy (Table 3), reveals multiple stabilising regions coloured cyan (light blue) or green (van der Waals). In contrast, the highest energy isomer (Figure 3b) shows a much sparser stabilising NCI distribution.

Figure 3. A NCI analysis of the weaker interactions present in the B3LYP+D3/TZVP/SCRF=DMSO computed transition state for (a) the lowest energy isomer (Table 3) and (b) the highest energy isomer (Table 3). The surface colour code indicates red = strongly destabilizing through to blue= strongly stabilizing.

The NCI analysis can be extended further by creating a spline of the reduced density gradients for two stereoisomers, and integrating based on the comparative values of the value of sign(λ2)ρ. The results (R=Ph) ...

Here, we report KIEs of a similar magnitude for the proline-mediated intermolecular aldol reaction between cyclohexanone and benzaldehyde. Although not experimentally verified, they are included here for future verification. The calculations have been performed using the lowest energy transition states, as established in the previous section. The predicted isotope effects reflect the synchronous nature of the reaction revealed by the IRC for R=Ph in exhibiting normal deuterium and carbon effects, and a small inverse oxygen effect.

Patil and Sunoj have computationally investigated the role of explicit solvent molecules in the modelling of the proline-mediated conjugate addition reaction in polar protic solvents, at the mPW1PW91/6-31G(d) and B3LYP/6-31G(d) levels of theory.29 The researchers proposed, that only via the explicit inclusion of two methanol molecules in a cooperative hydrogen-bonding network between the carboxylic acid proton and the oxygen atoms of a nitro group, could the correct stereochemical outcome of the reaction be predicted. This study however is based on the use of total calculated energies for transition states, rather than the more correct thermal and entropy-corrected relative free energies for the reaction profile. In addition to molecules of solvent, additives such as triethylamine30 and DBU31have been shown to play an important role in determining the selectivity of proline-mediated reactions through their explicit inclusion in transition state calculations.

Here, we investigate not the role of additive, but that of water in the Houk-List transition state. The first step of the catalytic cycle, which involves the formation of an enamine from the carbonyl compound and proline, liberates one water molecule. Potentially, this water could then participate in the subsequent reaction. Here, a single water molecule is introduced into the Houk-List model (R=Ph) as a passive solvent for one of the three oxygens via a hydrogen bond, augmenting the continuum solvation already applied. The effect this has on the relative energies of the anti and syn diastereomeric transition states, as well as providing a benchmark for comparison with proton relay mechanisms is shown in Table 5. Addition of just one explicit water molecule to the model was computed to induce little change in the computed free energy difference between (S,R) and (S,S) stereoselectivity, changing it from 2.97 to 3.15 kcal/mol.

Beyond a passive role, it is possible that a single molecule of water could participate directly in the Houk-List mechanism, acting as an active proton transfer relay between the proline carboxylic acid group and the incoming aldehyde (R=Ph) (Table 6). This results in the expansion of the ring size of the cyclic model by two atoms, thus allowing some stereochemical models previously excluded on the basis of strain to be included. Proton relay mechanisms in organocatalysis have precedent. One of the initial mechanistic proposals for the intermolecular aldol reaction, the HPESW reaction, involved a second molecule of proline acting as a proton transfer agent during carbon-carbon bond formation, based on the apparent observation of a non-linear effect.32 This proposal was later discredited through experimental studies confirming the absence of non-linear effects in the proline-mediated aldol reactions.33,34 Patil and Sunoj have also investigated the role of a proton-relay mechanism in hemiacetal-, iminium, and enamine formation for a model system mimicking the first step in the catalytic cycle of proline catalysis, at the mPW1PW91/6-31G(d) level of theory.35 It was found that protic additives, such as methanol, allow for significantly lower activation energies of these pathways. The reported energies did not include the effects of entropy, which would be expected to result in significantly higher free energies of activation compared to those based on total energies alone. Here we present computed free energy differences for the proton relay mechanism, isomeric with the passive mechanism described in the previous section.

Four features are noteworthy.

Figure 4. The computed intrinsic reaction coordinate for the proton-relay mechanism for R=Ph @B3LYP+D3/TZVP/SCRF=DMSO, showing (a) the relative energy and (b) the gradient norm. The red arrow indicates the location of the hidden intermediate. The calculation is archived at DOI:n44. (c) The IRC recomputed at @ωB97XD/TZVP/SCRF=DMSO showing the gradient norm and the more prominent hidden intermediate. The calculation is archived at DOI:n43

This mechanistic variation proposed by Hajos and Parrish36 for the intramolecular aldol reaction involves an initial proton transfer from the carboxyl group to the nitrogen of the enamine. This species can then react to form a C-C bond directly via a 6-membered ring transition state, accompanied by proton transfer from N to the carbonyl oxygen (Figure 5). The computed reaction IRC reveals an entirely synchronous process, with C-C bond formation coincident with proton transfer. The free energy however (Table 2) is 20.5 kcal/mol higher than the isomeric Houk-List model. The augmentation of the model with a proton-relay increases the overall activation energy even further (40.4 kcal/mol). This mechanistic variation reveals the incursion of two hiden intermediates after the transition state. As with the proton-relay variation, we can conclude that the Hajos-Parrish mechanism is also not viable for this reaction.

Figure 5. Hajos-Parrish mechanism, R=Ph (see Table 2) showing (a) the computed B3LYP+D3/TZVP/SCRF=DMSO geometry, (b) the IRC energy profile and (c) the IRC gradient norm, doi: n5d

(d) the IRC energy profile for the Hajos-Parrish mechanism, R=Ph with inclusion of one water molecule acting as a proton relay and (e) the IRC gradient norm for the proton-relay mechanism, with hidden intermediates indicated with an arrow, doi: n5n

Three models (Figure 6) were devised to evaluate the impact of structural changes upon predictions made using Houk-List model.

Figure 6. (a) 4-Piperidinone-Benzaldehyde-Proline, (b) Cyclohexanone-Pyrrole-2-carboxaldehyde-Proline, (c) Acetone-Pyrrole-2-carboxaldehyde-Proline. Bond lengths in Å computed at the B3LYP+D3/TZVP/SCRF=DMSO level.

The striking feature of all three variations is the difference in the predicted outcome that addition of a dispersion correction has Table 7). By model (c), with reduced steric congestion, the predicted ratio of the (S,R)/(S,S) diastereomers has inverted, but only when the dispersion correction is included. This result provides a compelling reason for including such corrections.

The Gaussian 09 program, revision D.01 was used for all calculations excepting the BSSE evaluation, where ORCA 2.9.1 was employed, and thermal corrections were applied based on computed normal vibrational frequencies. Kinetic isotope effects were computed from the difference in thermally corrected free energies obtained from the calculated Hessian (force constant) matrix and appropriate atomic masses for the isotopes. Intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) evaluations were obtained using the following keyword in the Gaussian program: irc(calcfc,recalc=10,maxpoints=200,maxcycle=40,tight,cartesian,stepsize=7,lqa) (the outcome of such calculations can be very sensitive to the imposed parameters). All calculations were routinely archived in both of two digital repositories (DSpace-SPECTRa and Figshare) and assigned a digital-orbject-identified (DOI). Some DOIs were contracted to a shorter form using the resource http://shortdoi.org/ NCI (non-covalent-interactions) were computed using the methodology previously describednci A Gaussian cube of the computed electron density at fine resolution was computed and converted to an NCI analysis using the resource at DOI: n5b, which is based on using the Jmol applet. The output of this process comprises a coordinate file (.xyz) and a compressed isosurface (.jvxl), which are visualised using the Jmol applet embedded in the interactive version of e.g. Table 2. This table has a DOI: ???

Computational modelling of the stereochemical outcome of catalysed solution-phase reactions has a stringent criterion for accuracy, defined in a sense by the equation ΔΔG‡ = -RT ln K. The predicted relative transition state energy ΔΔG‡ has to be sufficiently accurate to result in reliable values for K, the ratio of the concentrations of two stereoisomers. In practice, this means achieving a computed accuracy for ΔΔG‡ of < 1 kcal/mol or less for values of ΔΔG‡ of between 2-5 kcal/mol. The lower limit here being typical of moderately stereoselective reactions and the latter being towards the top end of the most highly stereospecific reactions known. This will require a reasonable exploration of conformational space, and mechanistic variations such as implicit passive solvation, and active proton-relay interventions, and this all to be achieved using methodology which can be implemented with reasonable time-turnover on modern computational resources. We have tested an improved variation on that used to establish the Houk-List model of the intermolecular aldol condensation catalysed by proline. A triple-ζ quality basis set is required to remove significant basis-set-superposition-errors, coupled with a dispersion energy correction to the B3LYP functional. Alternatively, more modern functionals which already include such terms can be used. The solvation treatment now possible is both more accurate and more self-consistent, since thermal corrections to the free energy are evaluated from frequencies determined within the solvation model. It is possible to explore more conformational space for the basic reaction, and to augment the mechanism with either passive or explicit intervention of small molecules such as water.

Whilst routinely achieving accuracies in ΔΔG‡ of < 1 kcal/mol is perhaps not entirely achievable at present, it surely will be in just a few years time, as the density functionals and other methodologies continue to improve. Here progress may be hindered by the relative lack of accurate experimental data determined under standard kinetic conditions. Achieving a stochastic exploration of the mechanism using molecular dynamics is perhaps rather further off for these relatively complex mechanisms.