Reporting scientific investigations in the form of a periodic journal is a concept dating back some 350 years to the 17th century.1 For much of that time, the only mechanism for dissemination involved bound paper (the "volume" or "issue"). This of course has changed in the last twenty years, at least in terms of delivery, but the basic structure and format of the scientific article has undergone less change. The article continues to interleave a narrative supported by reporting experimental data. The data is presented in the form of figures, tables, schemes and often just plain text in the highly visual form that humans can easily absorb. Often, only a small subset of the data actually available can be presented for reasons of "space". The online era, dating back perhaps 30 years, has allowed "supporting information (data)" to be separated from the physical constraints of the printed journal article and deposited with the publisher or a national library as a separate archive.

The logical connection between data present in the main article and its supporting counterpart is in fact tenuous; both sets of data continue to depend on the human reader to extract value from them. Text and data mining (TDM) however is making enormous strides2 in allowing machines to harvest data, being capable of far higher and less error prone throughputs than humans. This then facilitates human verification of assertions made in the narrative component of an article, or indeed the discovery of connections and patterns between a body of articles. The paper-bound article, including electronic emulations of paper such as the PDF format, is not well set up for a clear separation of the narrative and the data on which the former is so dependent. The two types of content are also caught up in complex issues of copyright; are the narrative rights and ownership held by the publisher or retained by the author? Is the ability to perform TDM an unrestricted one, or prescribed by the publisher? Unfortunately, the data component, which we may presume is not covered by copyright (one cannot copyright the boiling point of water) is often entrained in these complexities. Here we suggest a new model of how the scientific journal can take advantage of some of the many technical advances in publishing by emancipating the data from its interleaved co-existence with narratives.3 We reflect on how this might allow the journal to evolve in a manner more appropriate for a fully online environment, and present several examples.

A slowly growing innovation is the electronic laboratory notebook as the primary holding stage for the capture of data from e.g. instruments, databases, computational resources and other data-rich sources.4,5 This model can be represented as in Figure 1. The flow of data is primarily from data-source to notebook, and much less information is likely to flow in the other direction. When a project is complete, the data held in the notebook is then assembled into a narrative + data-visuals in a word processor and submitted in this latter form to a journal. The data, and its expression and semantics is rarely well preserved in this latter process. There is no communication at all in the reverse direction from the journal article to the notebook; if nothing else, the notebook security model would not permit this.

Figure 1. The standard model for the flow of data from the laboratory to the scientific journal.

Consider however an alternative model (Figure 2). It now incorporates perhaps the single most important game-changing technology introduced a little less than ten years ago, the digital repository in chemistry6 and other domains.7,8 This combines the concept of using rich (reliable) metadata to describe a dataset with an infrastructure that allows automated retrievals of the datasets, potentially on a vast scale. The other basic component of a digital repository is the idea of a persistent identifier for the data, one that can be abstracted away from any explicit hardware installation. There are other differences from the first model.

In the remainder of the current narrative, we will describe how a working implementation of this model was constructed.

Figure 2. A proposed model for the bidirectional data flows between the laboratory and the scientific journal.

Our starting point was computational chemistry, although solutions for molecular synthesis and spectroscopy have also been trialled.6 The basic resource for this is known as a high-performance-computing centre. Since the latter operates in a fully digital manner, it provides a good test-bed to construct an electronic-notebook customised for the purpose. Here will refer to it as uportal (Figure 3). The design of such a system has to factor-in requirements specific to computations:

Figure 3. The data flows between the uportal notebook and a digital repository.

The uportal notebook interfaces via a developer API11 to a digital repository to enable deposition there of:

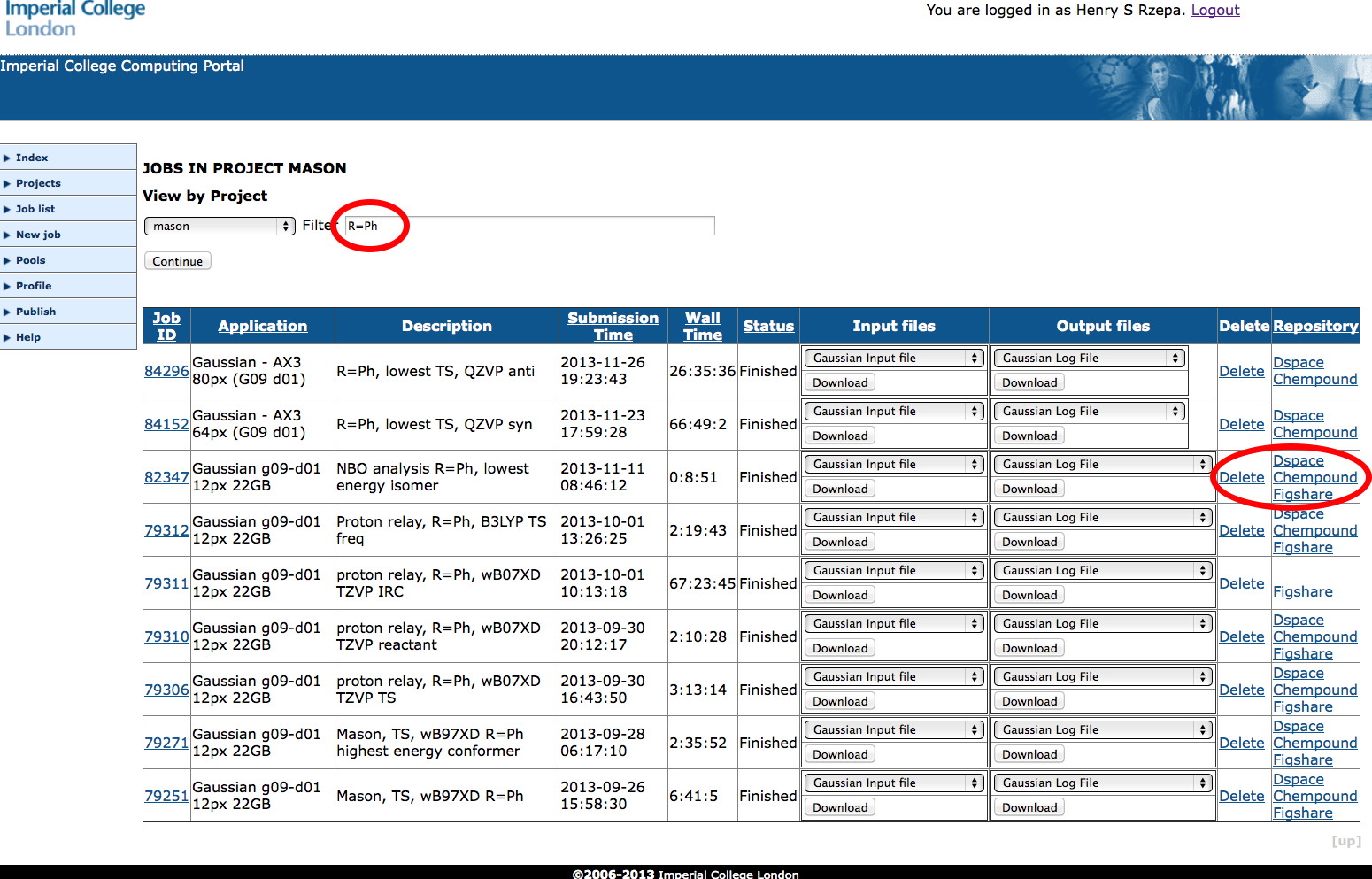

It is challenging and expensive to build/acquire/configure a general purpose electronic laboratory notebook system that can accomplish all these specialised tasks for a local environment. We believe it is more straightforward to instead construct a lightweight portal using standard scripting environments such as python or php. An overview of such a system can be seen in Figure 4, where some of these attributes are listed for each entry. As can be seen from the sequential ID, the system can easily scale to ~100,000 entries accumulated over a period of around seven years (about 10,000 entries each year). This was achieved by around 600 users distributed amongst staff, postgraduates and undergraduates. The last column shows the interface to the next component, the digital repository. The bidirectional nature is reflected in the capture of the assigned repository DOI back into the lite notebook if it has been published. Other actions include deleting the entry, or simply leaving it unpublished.

Figure 4. Uportal: a job submission and notebook system interfacing to a high-performance computing resource.

We have described elsewhere6 the principles behind our DSpace-based repository (SPECTRa), introduced in 2006. Two others have been added since then, Chempound13 and Figshare11. There is no limitation to the number of repositories that can be associated with any given electronic notebook.

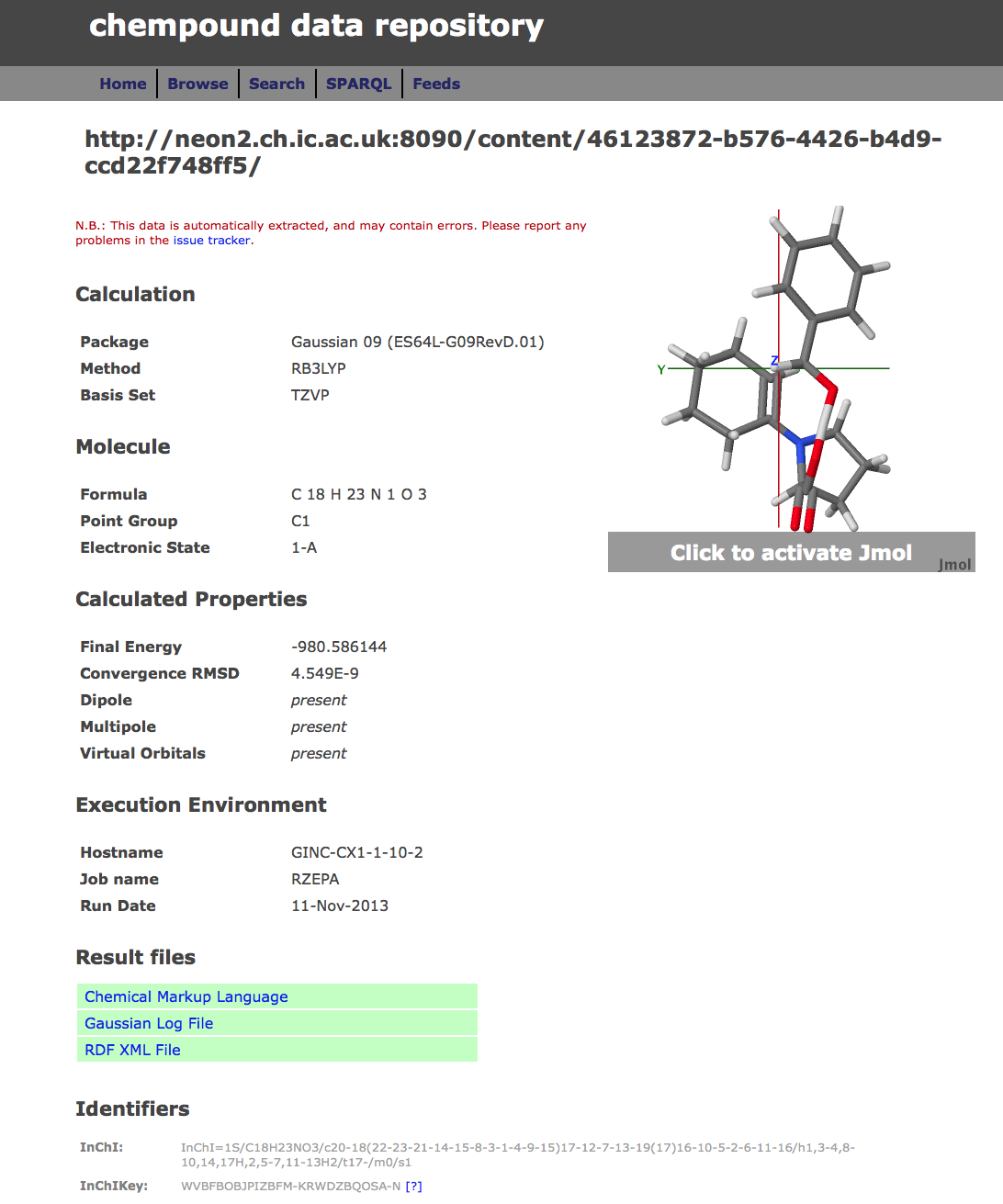

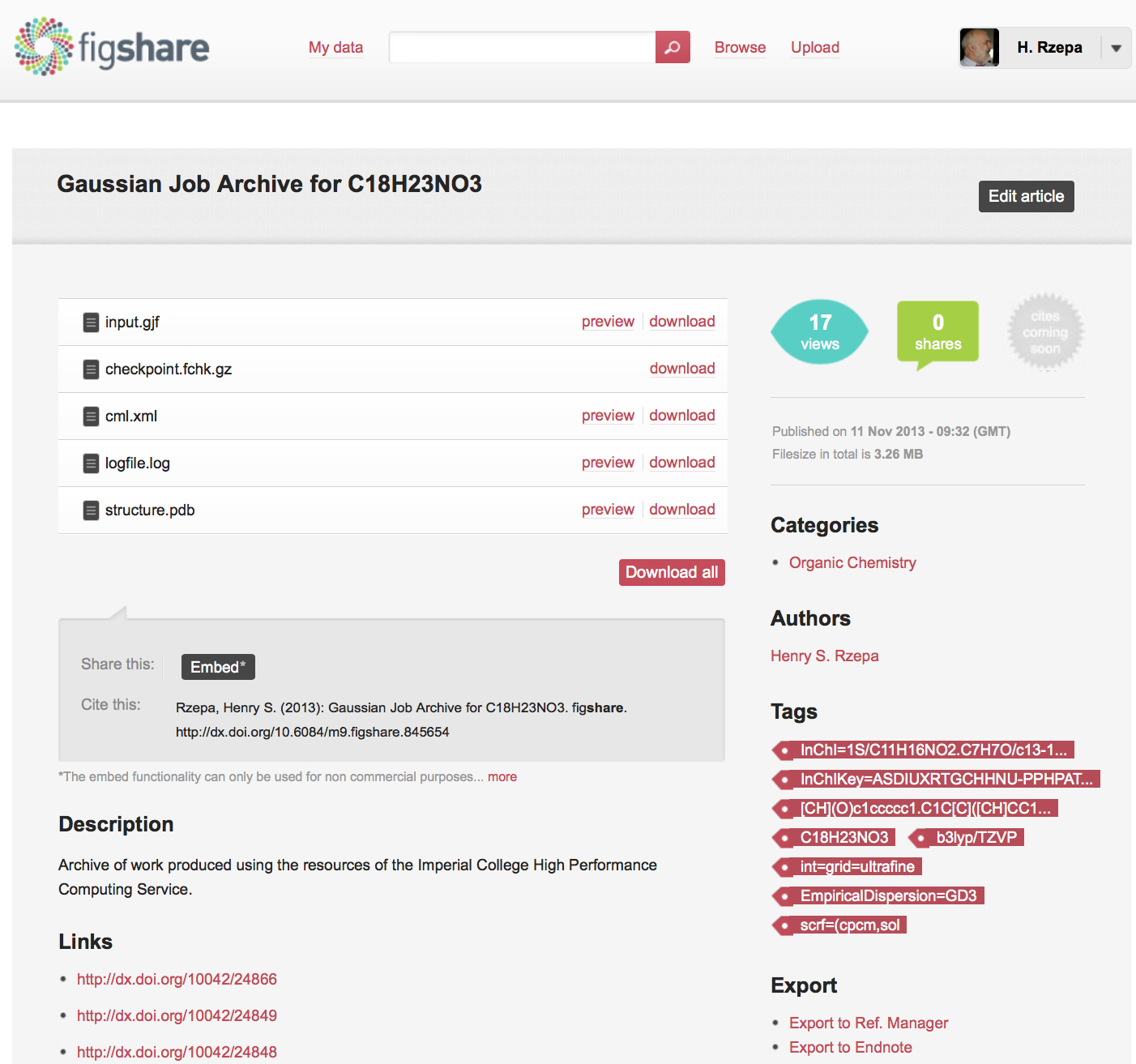

In general therefore, any dataset collected at the uportal as a result of a job submitted to the high-performance computing cluster can be simultaneously published into any combination of these three repositories. An example of how one particular deposited data or fileset is presented in these three repositories is shown in Figure 5, highlighting the auto-determined metadata and other attributes. The metaphor is that each dataset relates to a specific molecule with specific metadata for that molecule, and that this collection of data is then assigned its own repository identifier. Sets of such depositions can then be grouped into collections in the form of e.g. datuments (see below).

Figure 5. Repository metadata for the same dataset as sequentially published in (a) Dspace/SPECTRa, (b) Chempound (c) Figshare.

The Figshare repository differs in one regard from the other two. The initial deposition process reserves a persistent identifier for the object, inherits any project associated with the original entry from the uportal and creates a private entry within that project. At this stage, Figshare allows collaborators to be assigned exclusive permission to access the items in any given project, but the item is otherwise not open. Only when the project is deemed complete and submitted for publication need each entry be converted to public mode. One aspect of this process is not yet supported; a private but nevertheless anonymous mode to enable referees only to view the depositions as part of any review process. Currently, we make the data fully public even at the review stage, with priority afforded by date stamp and other metadata associated with the deposition.

Handles are analogous to Web URIs (uniform resource identifiers) in being a hierarchic descriptor containing an authority and a path to a resource. A technology for assigning and resolving persistent identifiers for digital objects (IETF RFCs 3650-2) was developed and is maintained by the Corporation for National Research Initiatives (CNRI). This has the following features.

The most common implementation of a handle by journal publishers is the Digital Object Identifier (DOI) System.9 A short-form of the standard DOI has recently been introduced which limits the identifier length to seven characters, and can be as few as three, the purpose being to facilite their use by humans. Handles are typically resolved through using http://hdl.handle.net or http://doi.org. These resolvers can display the records returned from the prefix server via the syntax:

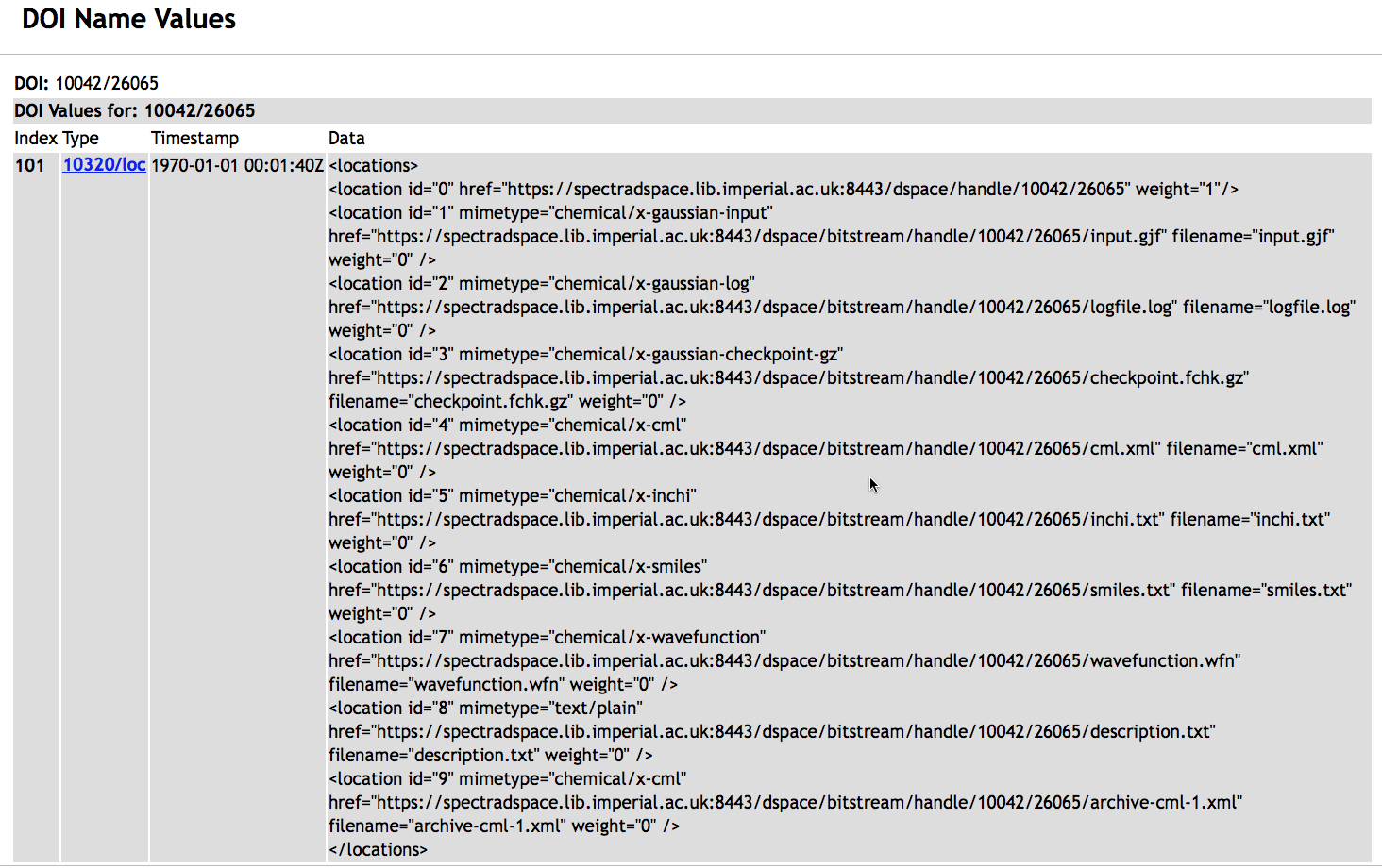

It is more common is to use the Handle resolver to immediately redirect the client to the destination page, often also referred to as the "landing page", using a "URL" record type. Although it would be possible to also assign such a URL record to individual data files, this rapidly becomes unwieldy and the associations between related files are lost. Such URL records also have the limitation that there is no easy way of specifying what action is required for the file, the default being simply to attempt to display the contents in the browser DOM (document object model). A standard more flexible way is therefore needed to directly specify the individual files within a deposited record, and one which may be off the landing page. This can in fact be achieved by an extension to the handle system, the poorly-known Locatt feature of the "10320/loc" record type that was developed to improve the selection of specific resource URLs and to add features to the handle-to-URL resolution process.15 This type includes an XML-encoded list of entries, each containing:

The servers hdl.handle.net or doi.org accept the URL-encoded "?locatt=key:value" and return the URL of the first entry matching key=value. We define the keys "filename" and "mime-type"16 in our custom DSpace handle records (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The response returned for a query http://doi.org/10042/26065?noredirect showing the filename and mimetype records.

This now works as follows:

The most valuable feature of this extended experimental system is that the resolvers hdl.handle.net/api/10042/26065 or doi.org/api/10042/26065 return the JSON-encoded (JavaScript Object Notation) full handle record, which we use for processing in Javascript. There do remain issues which will need eventual resolution.

With an system established which can directly and automatically address individual files (objects) held in a repository store, we can now consider how more complex object such as datuments8 might be constructed. Consider a table or a figure which can be built8 from basic HTML5/CSS3/SVG/Javascript components, as is typical for a complex marked-up web page. The complete collection may number 100s of files. In chemistry, such datument collections have been in use since 2006,17 with descriptors such as Web-enhanced-objects (WEO, by the American Chemical Society) or interactivity-boxes. As these descriptions imply, they are a combination of data together with a scripted environment that renders the data into an interactive visual presentation to the reader (a datument).9 Most of the existing examples are interwoven with the narrative of a journal article17 and occur in the HTML version of the article, whereas a static equivalent is presented in the printable PDF version. The infrastructure described above now allows us to formally separate such datuments from the narrative by depositing the data fileset into a repository and assigning it a persistent identifier of its own. The datument can then be re-absorbed back from the repository using e.g. an <iframe> declaration.

We have now created a number of such datuments on the Figshare repository, which have the following features:

<a href="javascript:handle_jmol('10042/26065',';frame 21;connect (atomno=1) (atomno=11) partial;')">log</a>, with components listed below:

<iframe src="http://wl.figshare.com/articles/840483/embed?show_title=1" width="850" height="300" frameborder="1"></iframe>

the effect being shown in WEO 1. In principle, the iframe declaration could itself be derived purely from the datument DOI using the locatt selection method described above; in this specific instance, it was obtained manually from the Figshare DOI landing page. It is also possible that this HTML element will be superseded by the use of a link element which is regarded as having superior document properties: <link rel="import" href="/path/to/imports/stuff.html">

The functionality implemented in the resolve-api.js script is linear. One or more persistent-identifiers for datasets specified in a datument are each resolved using a handle server into 10320/loc handle record types pointing to a data-repository server. This returns the specified files to the calling datument, which itself can be requested by a journal server via its own persistent identifier. A total of up to four services in possibly four locations can involved in this sequence, each being a potential point of failure. Here we briefly discuss what redundancies could be built into the system.

The general repository structure would be as follows:

Repository 1 Handle records URL - URL of landing page (repository 1) URL - URLs/persistent identifiers of landing page (e.g. repository 2) URL - URLs/persistent identifiers of landing page (e.g. repository 3) 10320/loc - locations of files at repository 1 Repository 2 Handle records URL - URL of landing page (repository 2) URL - persistent identifier for additional deposition (e.g. repository 1) URL - persistent identifier for additional deposition (e.g. repository 3) 10320/loc - locations of files at repository 2 etc.

This scheme relies on the alternative resources having the same or a similar handle record structure, including the 10320/loc type. Currently, only our DSpace/SPECTRa server has this specified, so the scheme above is not yet capable of practical resolution. It is nevertheless useful to include all instances of alternative depositions in the handle record if possible, in anticipation of other repositories implementing this scheme.

In the 10320/loc scheme, locatt is a selection method that selects a location based upon a specified key-pair attribute. This scheme also allows two other selection methods, country and weighted, specified by a chooseby attribute.15 If this attribute is not defined, it defaults to locatt,country,weighted. Our implementation (which allows the value of chooseby to default) uses locatt followed by weighted. We suggest it is good practice include an explicit chooseby attribute in the Handle records to anticipate any changes or enhancements in the repository structures. We also note that increasing consideration is being given to country records, since it can be desirable to select these based on the legal frameworks in place for cloud-based data.

The redundancy model described above is suitable for a tightly coupled set of repositories into which deposition is managed by e.g. the uportal front end. Specifications for a complementary solution known as ResourceSync have recently been published19 to enable remote systems to remain in step with their evolving resources. There are no working implementations yet which could be demonstrated here.

Data emancipation along the lines of the model set out in Figure 2 has been used in five articles to date19-23 (six if you include this one).

In all five cases, much of the data originated from the quantum-modelling of the systems controlled using the uportal. The individual calculations were published into both Dspace and Figshare simultaneously as public objects. The assigned DOIs were then incorporated into tables and figures as hyperlinks using HTML. For articles 1-3 and 5, explicit data files were also included in the file collection and the complete set was then converted to a datument, uploaded to the Figshare repository and then itself assigned a DOI (the one quoted above). The reader can either retrieve this local copy of the data and view it in Jmol, or use the original DOI for that item to download a more complete set of set which includes the input specification which defines how the calculation was performed, and a checkpoint file containing the complete set of calculated properties. For the fourth article above, no local copies of the data files are present in the complex data object, and the calculation log files are retrieved on-demand from the original repository (in this instance DSpace/SPECTRa). There is one exception to this type of retrieval. Some of the original data sets were converted into electron density cubes using the calculation checkpoint file and a non-covalent-interaction (NCI) surface was then generated. This was as two files, a .xyz coordinate file and a .jvxl surface file; such operations can take 10-15 minutes or longer per molecule and are too long to be implemented as an on-demand interactive process. These specific surface files were therefore included into the datument as local files.

The model above was clearly developed to handle and illustrate the type of data we are interested in; it is not a generic solution for chemistry! But it serves to demonstrate that the entire workflow can be successfully implemented, which suggests that solutions for many other kinds of chemical data should be developed.

Search engines are starting to appear which focus on citable data. For example, all the metadata associated with persistent data identifiers issued by DataCite14 is available for querying. Thus:

http://search.datacite.org/ui?q=InChIKey%3DLQPOSWKBQVCBKS-PGMHMLKASA-N

will return all deposited data objects associated with the InChIKey chemical structure identifier30 LQPOSWKBQVCBKS-PGMHMLKASA-N. As the "SEO" (search engine optimisation) of the metadata included in the depositions becomes more effective, so too will e.g. searches for molecular information held in digital repositories. Similar features are also offered by Google scholar31 and ORCID (open-researcher-and-collaborator-id)12. A search using either of these sites for one of the present authors reveals multiple data-citation entries from both the DSpace/SPECTRa and Figshare repositories. Although data-citations cannot be directly compared with article citations in terms of impact, the infra-structure is appearing to construct useful altmetrics to do so. Thus one example of how "added value" can accrue is illustrated by a resource32 harvesting metadata from the data repository Figshare11, the ORCiD12 database of researchers and collaborators and Google Schoolar.31 This information includes metrics which allow usage of the data to be estimated, and hence rather indirectly some measure of its scientific impact.

A two-component narrative-data model for the journal article (Figure 2) has the potential for solving one major current problem associated with scientific journals; the serious and permanent loss and emasculation of data from its point of creation in the laboratory to its final permanent presentation to the community in the published article. A very recent publication serves to illustrate the serious extent of the data loss.33 A significant computational resource was used to create 123,000 sets of optimised molecular coordinates in an impressive exploration of the conformational space of four pyranosides. Only 907 of these coordinate sets are available via the article supporting information, and they are presented in the form of a double-column unstructured monolithic PDF document containing page breaks and numbering and with very little associated metadata for each entry. A fair amount of effort would be required by the reader of this article to (re)create a usable database from this collection for further analysis. Absence of what could be regarded as key data is unfortunately often the norm rather than the exception. Some reported data can be recast into a structured re-usable form by data-mining techniques, but where it occurs has traditionally been conducted by commercial abstracting agencies, the substantial cost of which is also passed back to the scientist. In the example described here, if the data is absent in the first place, it cannot be recovered by any form of data-mining. It is worth at this stage noting a recent and concise declaration of principles known as the Amsterdam Manifesto34 regarding data-sharing, which are reproduced here in full;

Of particular note are articles 6 and 7 above, which we address as described above using the 10320/loc records. Article 8 proposes that credit for data citation should be facilitated, which resources such as ImpactStory32 are starting to do.

The clear separation of narrative and data also addresses the vexed issues of copyright; data need no longer be constrained by limitations and costs imposed upon the narrative. There are costs of course associated with the data; the repositories must have a sound business model to ensure their long term permanence. Whether these responsibilities are borne by the agencies where the research is initially contracted, or by new agencies set up for the purpose will be determined by the communities involved.

Other than the infrastructures implicit in e.g. Figure 2, there is also the issue of how to persuade the authors of a scientific article to create the two components we propose. The narrative is straightforward, but can authors be persuaded to use and create the data objects? Very few are currently well versed or confident in using the HTML5/CSS3/SVG/Javascript toolkit to write scientific articles, although it is worth noting that this combination of tools is specified in an open distribution and interchange format standard for digital publications and documents known as epub3.35 As adoption of such standards increases, so will familiarity with the concepts. An interim solution for promoting adoption may lie in the creation of standard templates; most of the complex detail is actually carried in Javascript and stylesheet declarations that need not be edited. They can be easily transcluded into a document template via header declarations. Indeed, almost the only actual code that they need be aware of is that shown earlier:

<a href="javascript:handle_jmol('persistent identifier', 'presentation script')">linked hypertext</a>

A more challenging problem is that most authors would see little reward in the current system for undertaking such tasks. Such rewards accrue from the narrative they present (be it scientific article or Ph.D. dissertation) and not currently from the data they associate with that narrative (except of course that the narrative would not stand on its own if no data had been presented somehow). Here, the scientific community must agree that preserving data and curating it for the future is a worthwhile activity and bestow the appropriate rewards for doing so, or indeed apply sanctions if it is not done. Technically at least, there is nothing preventing the scientific journal from evolving in this manner.